I led an introductory Realtalk workshop for Shawn and Konlin at Dynamicland. It took place on Nov 2 and Nov 12, about 10 am to 5 pm each day.

Because Shawn and Konlin already had some exposure to Realtalk and were already motivated to start making things, my primary goal was to help them understand Realtalk's model of computation -- the "physics" of Realtalk. I saw a lot of confusions about this in earlier conversations with Konlin.

In the past, we've introduced people to Realtalk by having them wish for illuminations and match spatial relations, but the projects that Shawn and Konlin were talking about seemed to demand a deeper understanding of how statements and rules actually work.

My approach was to improve Realtalk's visibility so statements and matches could be seen directly, and center the workshop entirely around making and matching statements, rather than using functionality from the rulebooks.

Agenda: Day one

Setting up a space

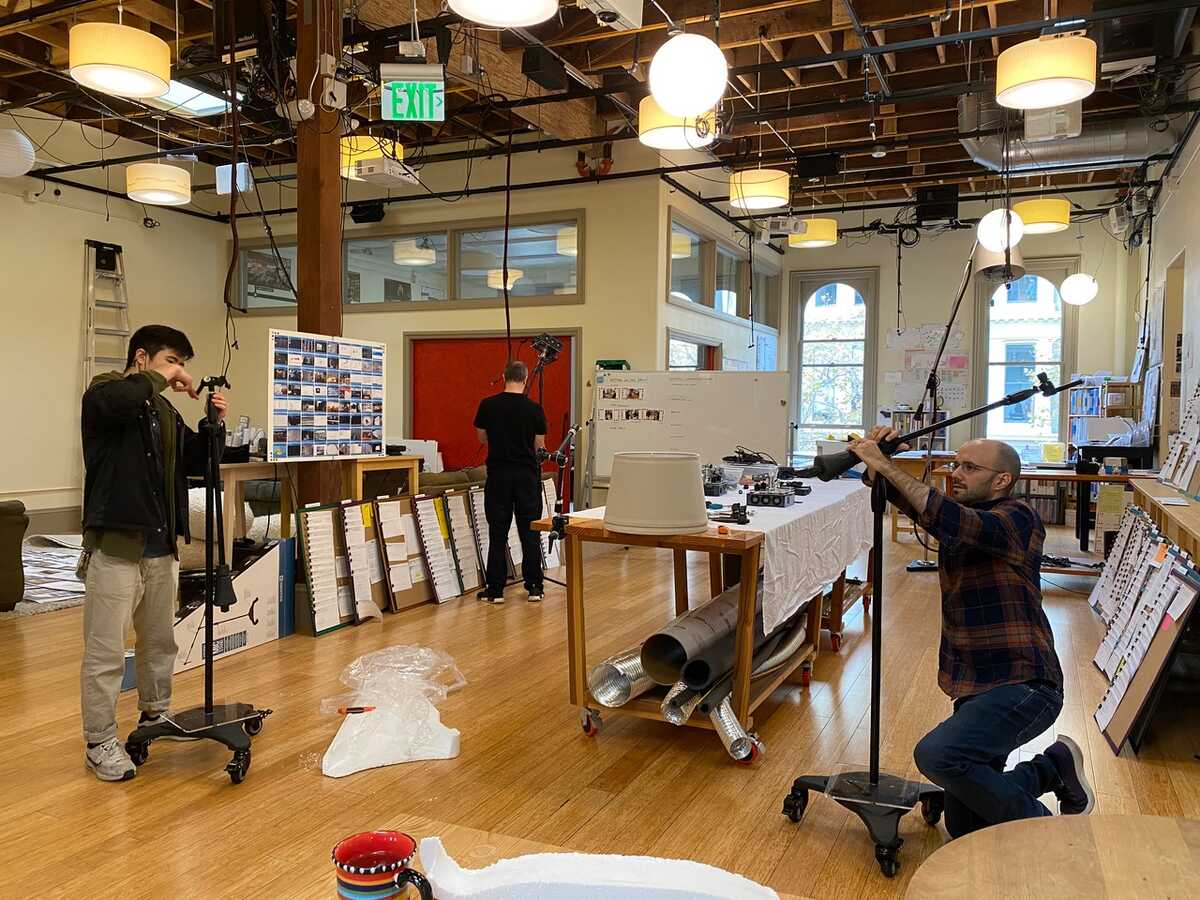

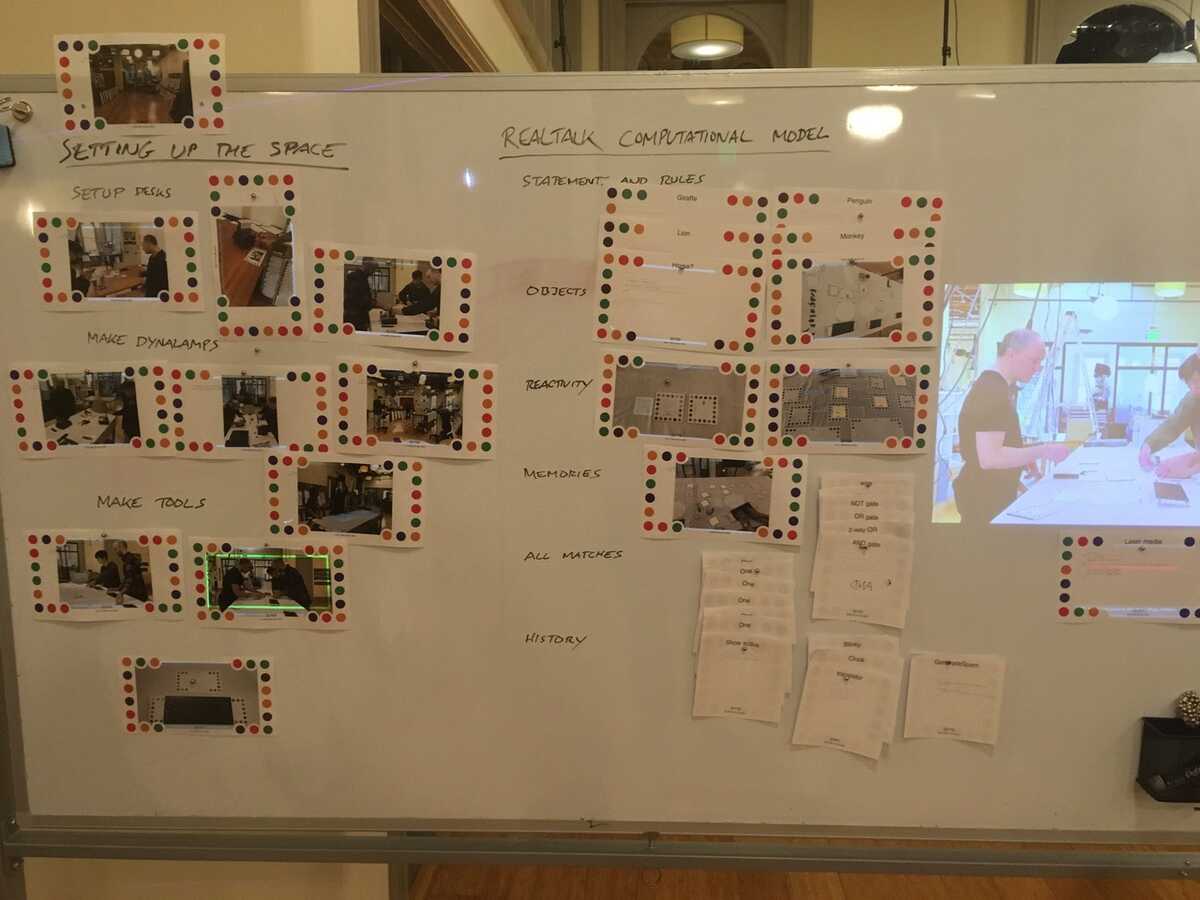

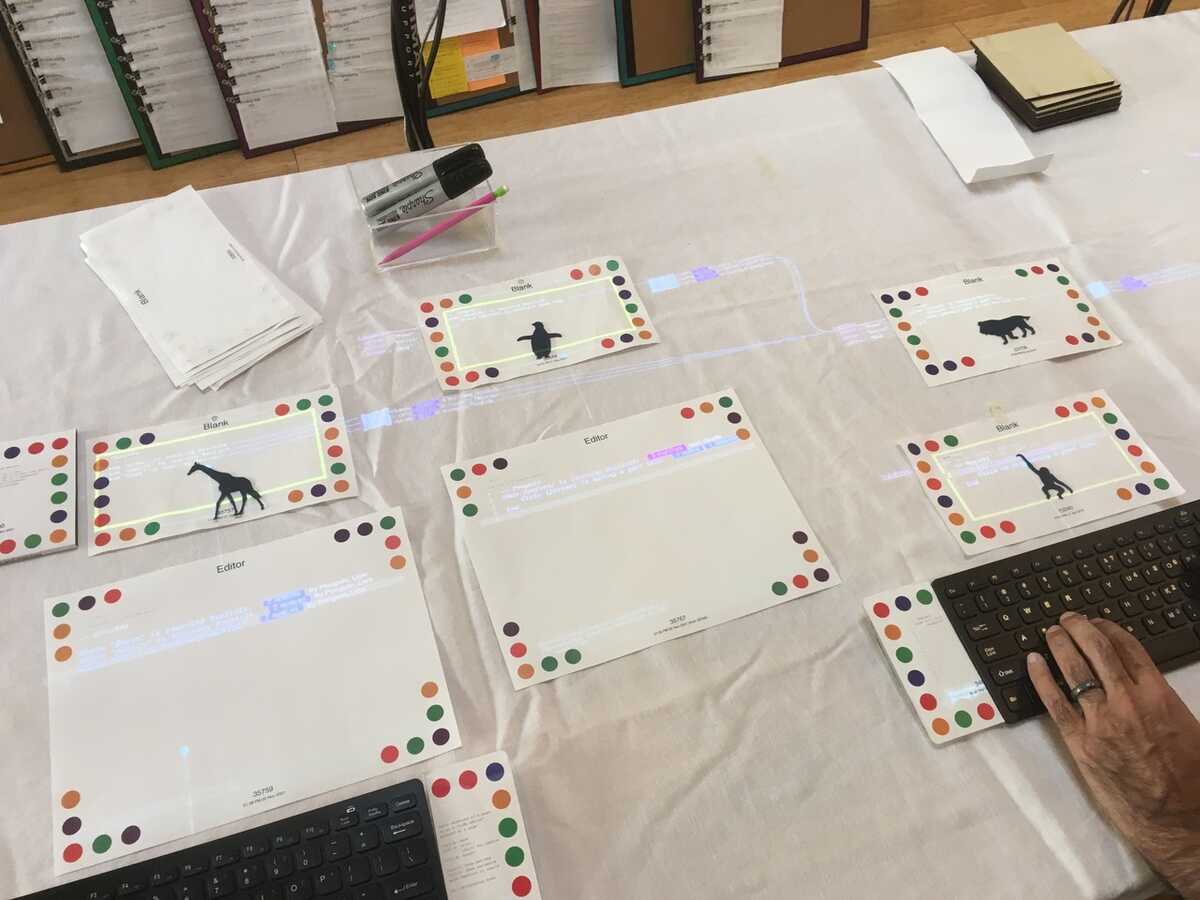

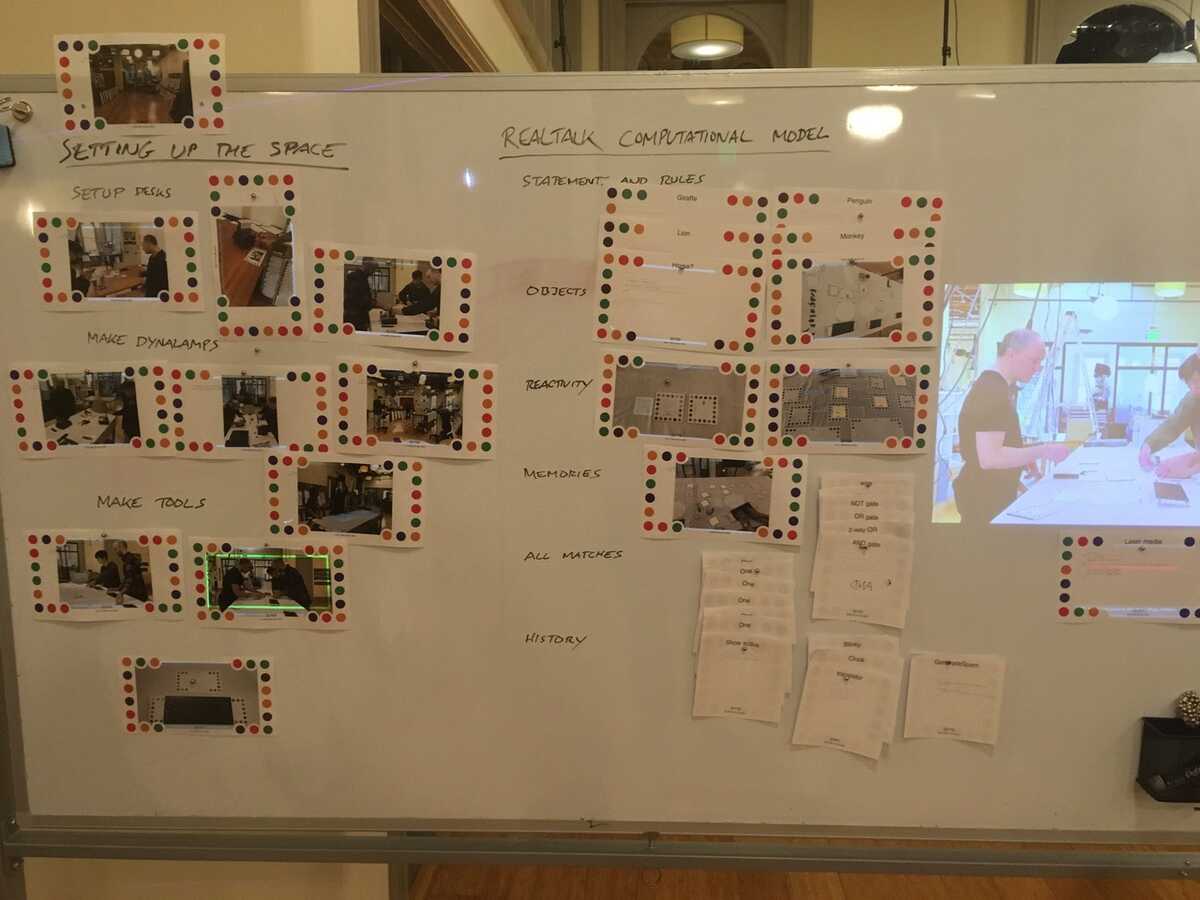

We started with a large open area of lab, surrounded by rulebook posters but otherwise empty. We brought over a whiteboard and I wrote out the agenda. I had them scan the QR code for "From PC to printer" on their phones, so they could take photos that would immediately print out as Realtalk pages. As the day proceeded, we put our photos and pages up on the whiteboard next to the agenda, to form a gallery of what we'd done so far.

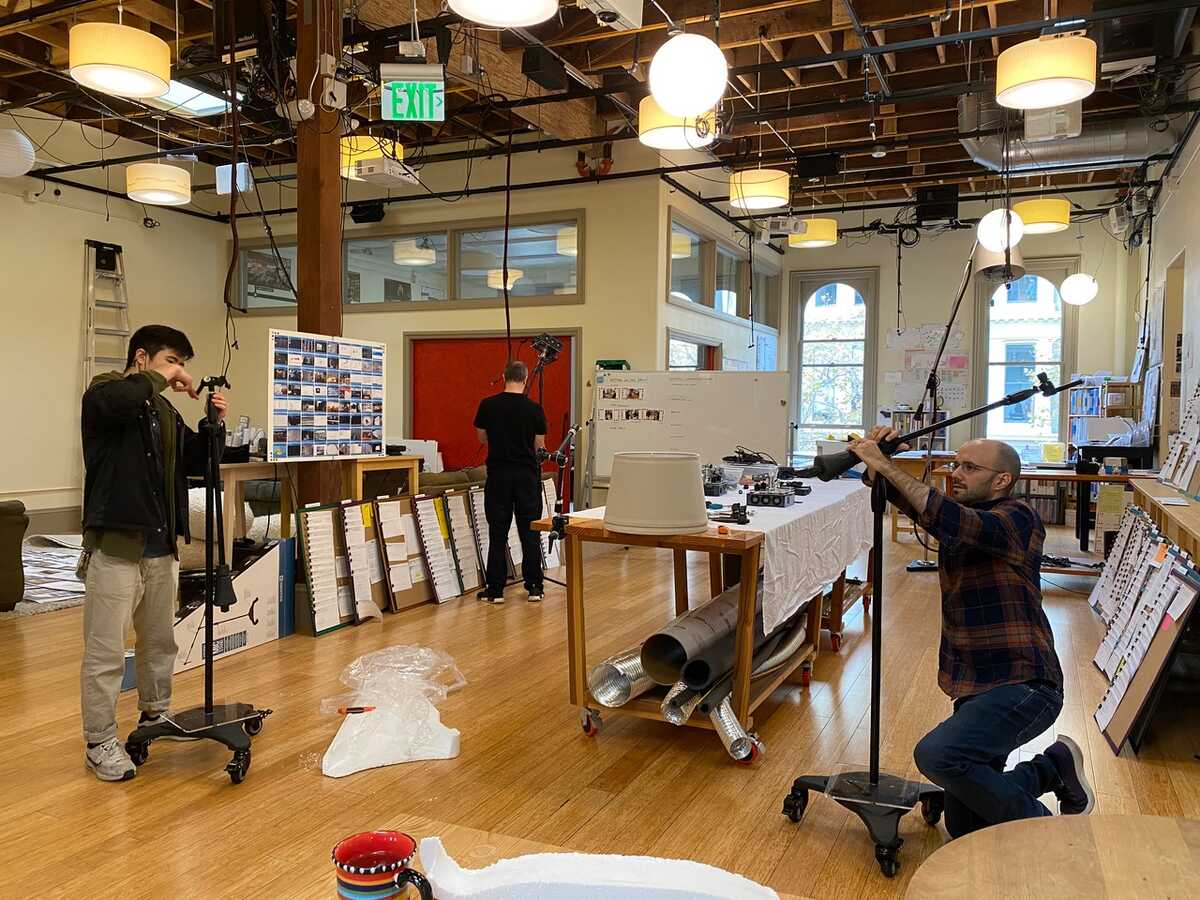

We dragged over two work tables to make one long table, and set up a tablecloth (to make visualizers on the supporter more visible), paper cutter, trash can, printer, pens, etc.

Building Dynalamps

They each unboxed a projector and assembled a Dynalamp head from parts, then unboxed a mic stand and assembled an entire floor lamp. We set up the two lamps side-by-side on one side of the table. I provided an already-installed NUC to sit at the base of one of the lamps, and they routed wires to it. After some NUC trouble (see below), we got the lamps up and running. I calibrated the lamps and configured the printer. They took keyboards and assigned them.

While they were building, I set up another lamp to point at the whiteboard, and made a page so you could laser the photos and videos.

Making tools

I lent them one Blank. (The "ur-Blank".) From there, they made their own Blanks and Editors. They also made a "Do not run", to learn how to make a tool square.

Simple statements and rules

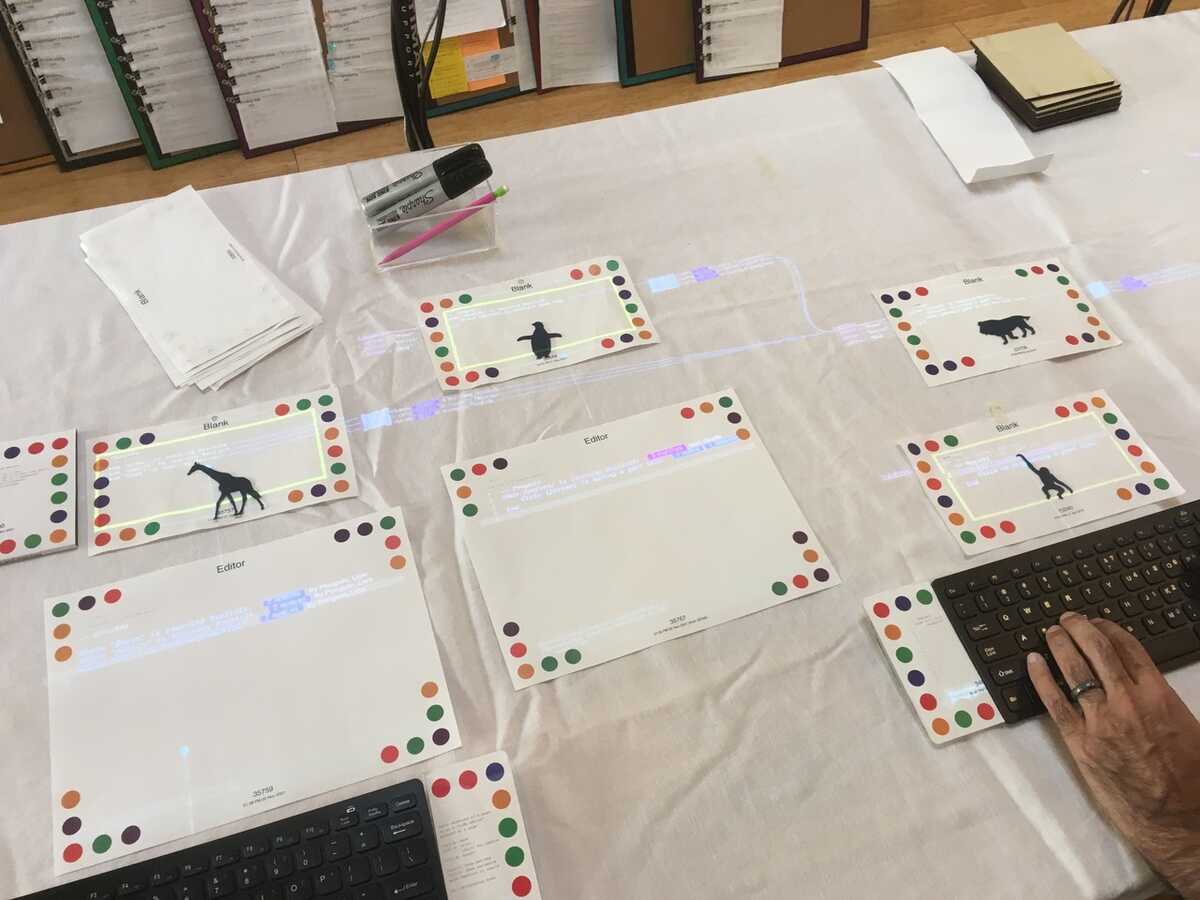

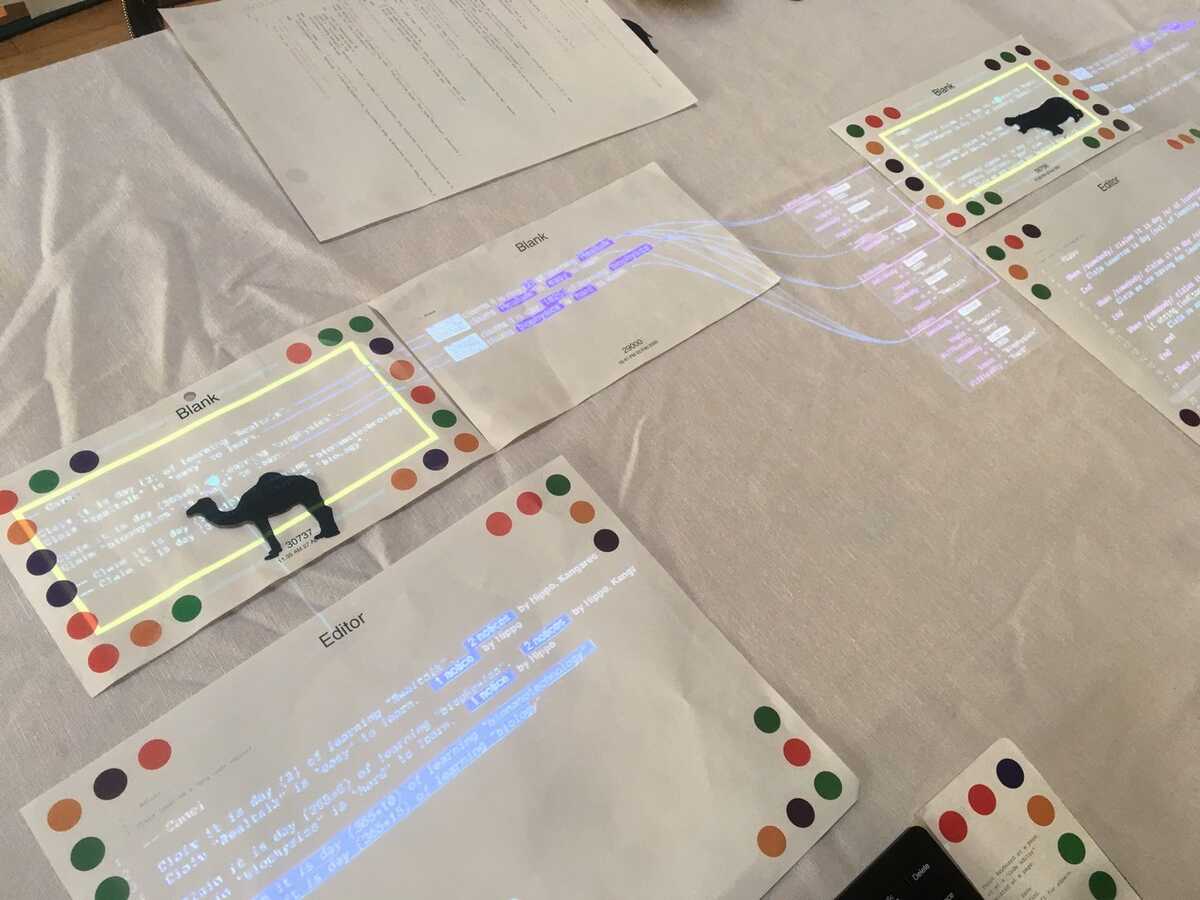

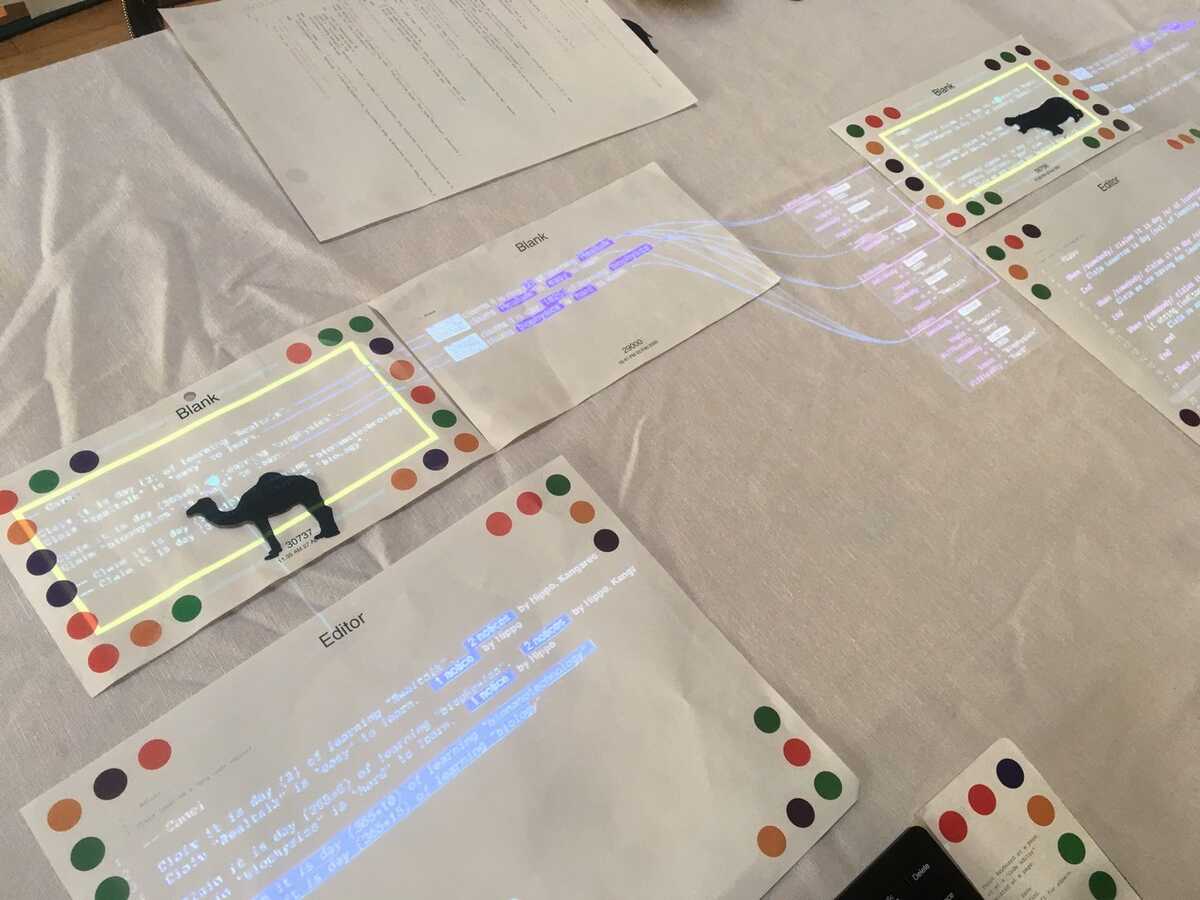

Because we would be working mostly on Blanks, we chose laser-cut animal shapes to put on our Blanks, and titled the page after the animal, so we could see who was making which statements. The "Show statements and matches" tool was present most of the time, so we could always directly see the statements made by every page, and see them flowing into matching rules. I wanted to give the mental image of the statements lying out on the table, and rules noticing them on the table.

We started with statements and rules with no parameters, such as

Claim we are learning Realtalk.

and

When we are learning Realtalk:

Claim we are having a good time.

End

and I tried to emphasize how statements are consequences of other statements. Then, "or" relationships using multiple rules:

When we are learning Realtalk:

Claim we are having a good time.

End

When we are eating lunch:

Claim we are having a good time.

End

and "and" relationships using multiple clauses:

When we are learning Realtalk,

we got enough sleep:

Claim we are having a good time.

End

Throughout the workshop, after demonstrating each point, I would try to offer a challenge, usually by having my page make some statements and asking them write rules that respond with particular statements. Because all statements were shown, simply making a statement itself was generally a good enough visible goal (as opposed to, say, wishing for a label).

Statements with parameters

Making statements with number, string, and table parameters. Matching statements such as

Claim "Shawn" is learning Realtalk.

Claim "Konlin" is learning Realtalk.

with rules such as

When /person/ is learning Realtalk:

Wish (person) gets to use Realtalk later.

End

What happens when there are multiple matches. Match variables.

Objects and you

Making statements with object parameters, such as

Claim (you) is learning Realtalk.

and rules such as

When /p/ is learning Realtalk:

Wish (p) is highlighted "yellow".

End

The ambient cloud of statements. We pointed "Statements about left" at a page to see all of the statements about it. We followed some of these statements back to their source, taking out the rulepage responsible and examining it (e.g., who is drawing text on the Blank pages?) Emphasizing that every statement about an object is made by some other object in the room.

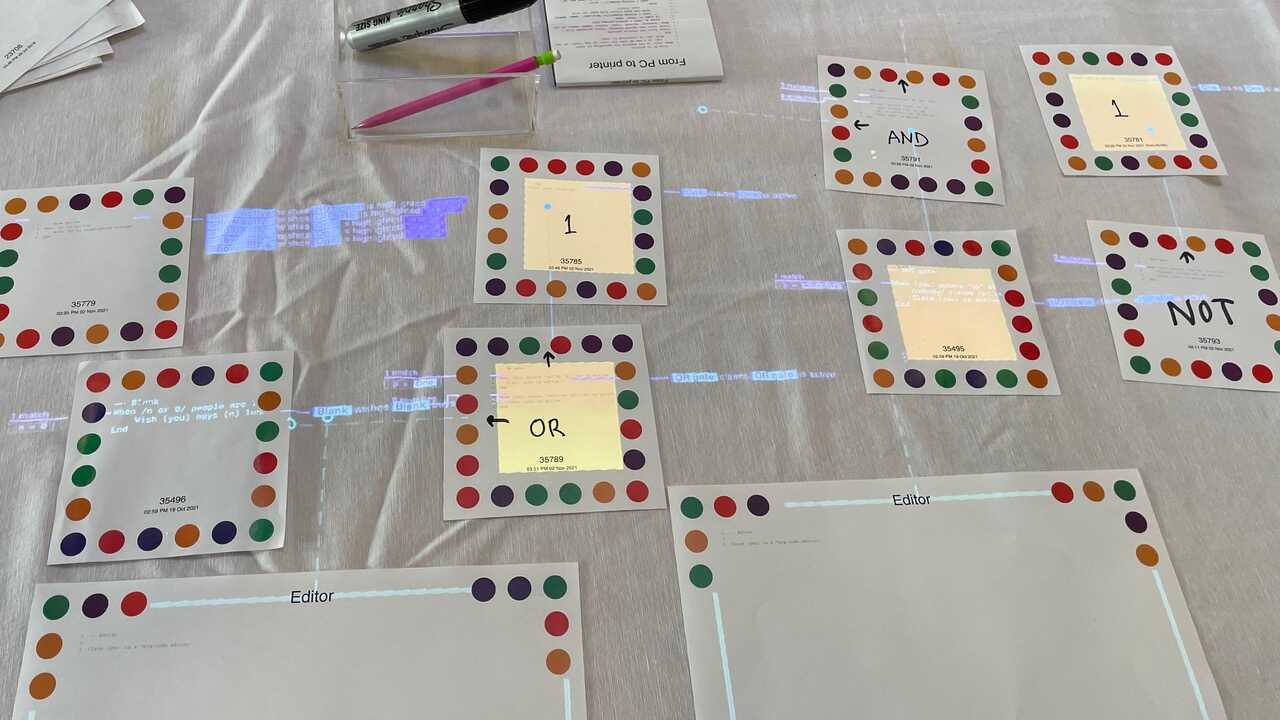

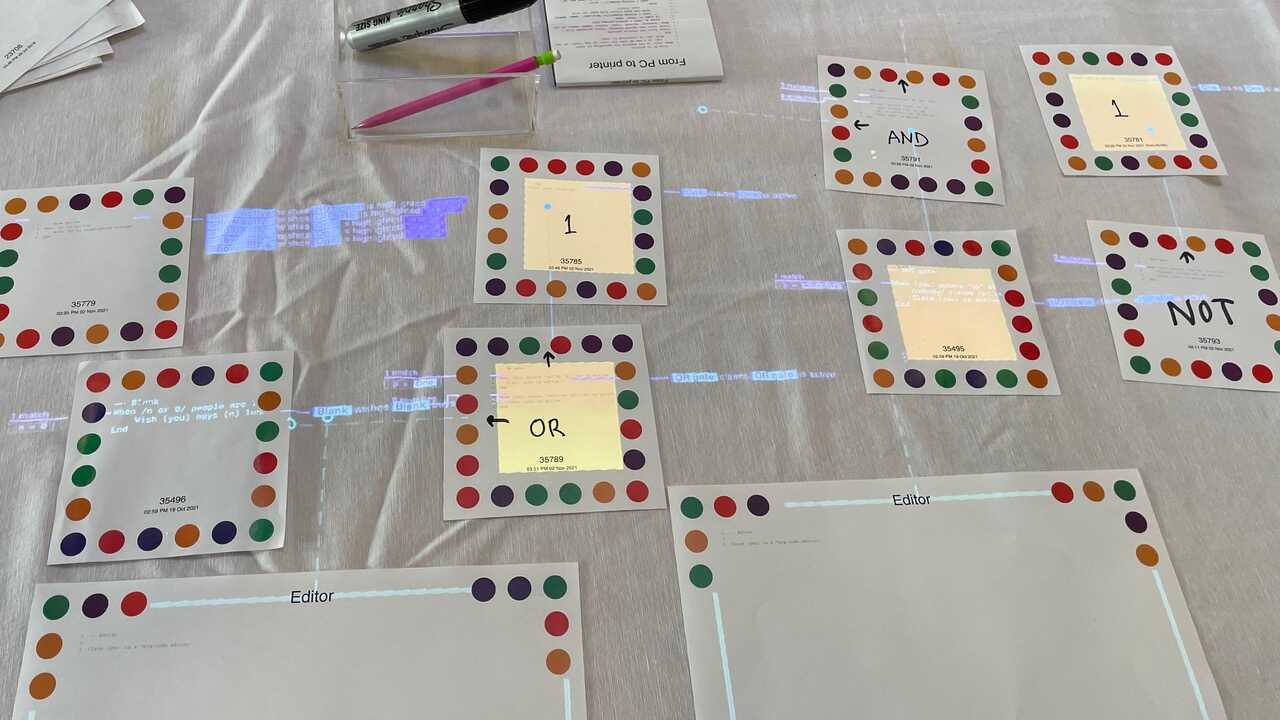

Reactivity

Logic gates represent a model of computation that is both (somewhat) familiar and much more like Realtalk than conventional imperative programming, and I thought building logic circuits in Realtalk could help override imperative instincts about mutating variables, etc.

Starting with "One":

Claim (you) is active.

and "Show active":

When /p/ is active:

Wish (p) is highlighted "orange".

End

they made:

- "Wire" (active if the object to its left is active)

- "AND" (pointing up and pointing left)

- "OR" (point up and pointing left)

- "NOT" (using /nobody/)

Konlin diverged a bit to make a "transistor".

They then made a "Clock":

When the clock time is /t/, (t%1 < 0.5):

Claim (you) is active.

End

which blinked prettily.

Memories

One of the points of the logic gate exercise/analogy was the reminder that combinational logic is always stateless and reactive, and if you want to do something across time, you need to explicitly introduce stateful elements. In circuits, these are latches/flip-flops, and in Realtalk, these are memories.

I demonstrated memories with a page that counts up. I planned to have them make a latch, and we could then play with clocking synchronous circuits, as an analogy to Realtalk's convergence and tick. For various reasons (see below), the introduction of memories at this point was not successful.

We were also starting to get fatigued by this point, so we called it a day. Due to scheduling conflicts, the next day we could get together was 10 days later.

Agenda: Day two

While the first day generally followed my planned agenda and was organized around topics, the second day mostly consisted of improvised challeges based on my sense of where their boundaries were.

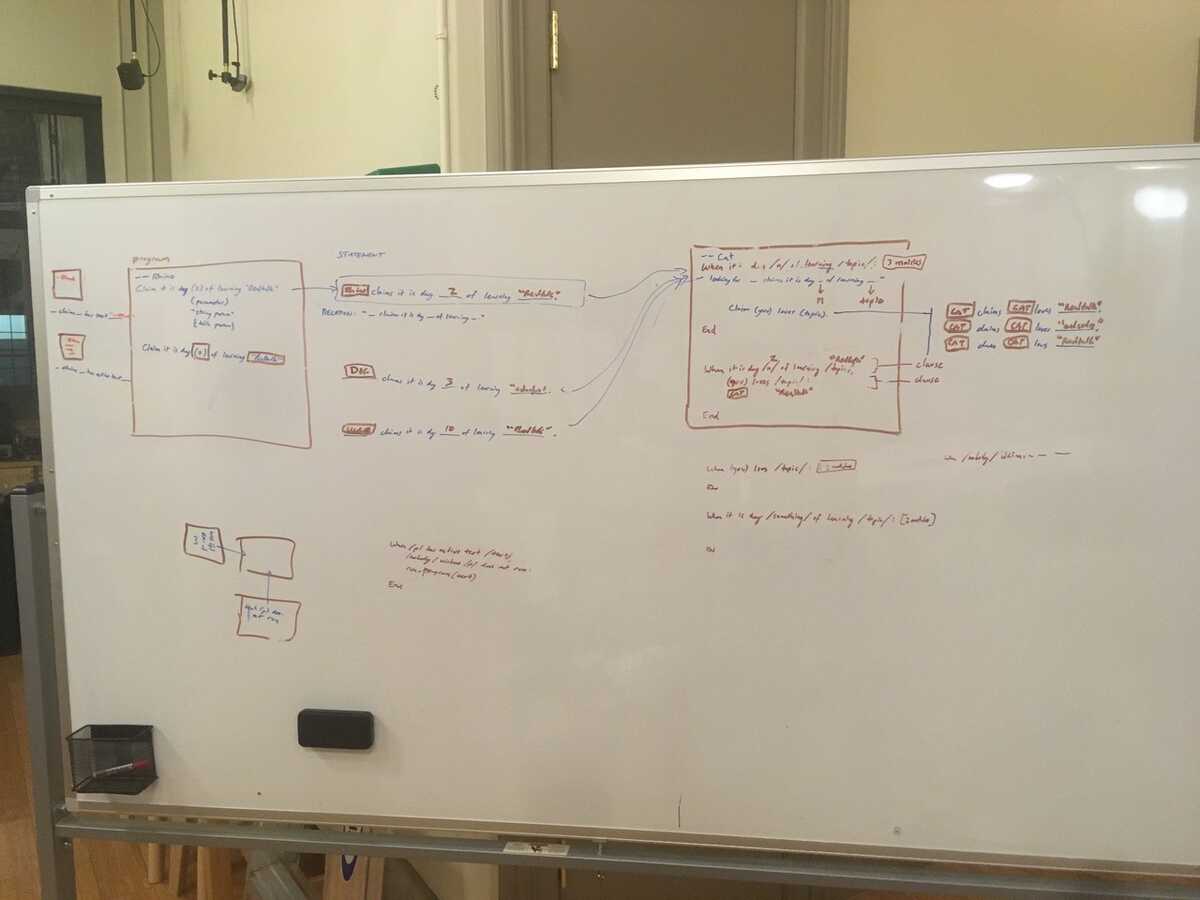

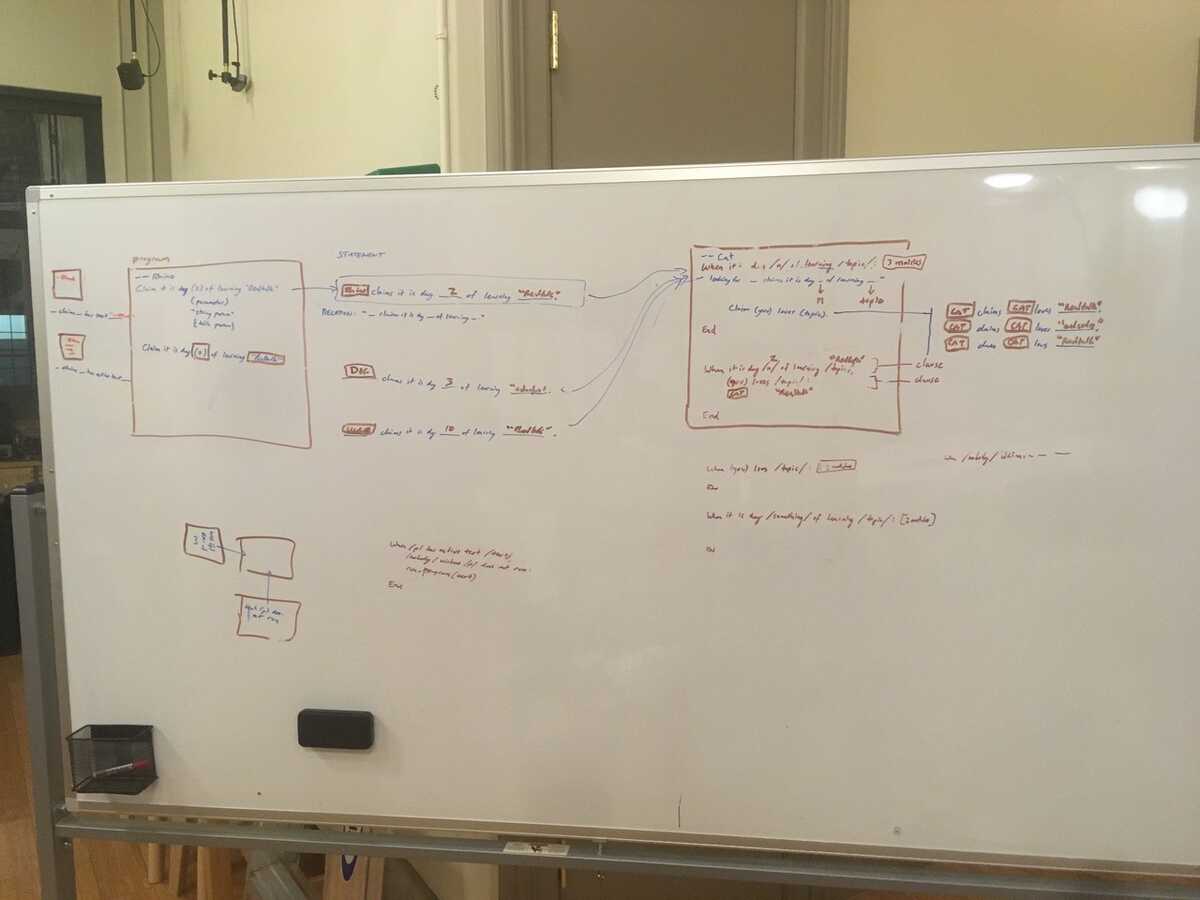

Whiteboard lecture

I started the day with a whiteboard lecture, with the main goals of making clear exactly what a statement was, what a relation was, and how a clause in a rule will only match statements with the exact relation. And more generally, that a statement only has an effect if there is some rule to match it, and a rule is only meaningful if there is someone to make a matching statement. They asked a lot of questions.

Statements and rules, redux

Back at the table, I made statements such as

Claim it is day (2) of learning "Realtalk".

Claim "Realtalk" is "easy" to learn.

Claim it is day (365*5) of learning "biophysics".

Claim "biophysics" is "hard" to learn.

Claim it is day (365*15) of learning "biology".

and challenged them to write rules that responded in certain ways, e.g.:

When it is day /n/ of learning /topic/:

Claim tomorrow is day (n+1) of learning (topic).

End

When it is day /n/ of learning "Realtalk":

Claim we are having fun learning Realtalk.

End

When it is day /n/ of learning /topic/:

if string.find(topic, "bio") then

Claim we are having fun learning bio stuff.

end

End

When it is day /n/ of learning /topic/,

/topic/ is /difficulty/ to learn:

Claim we have spent (n) (difficulty) days learning (topic).

End

When it is day /n/ of learning /topic/,

/nobody/ claims /topic/ is /anything/ to learn:

Wish to know the difficulty of (topic).

End

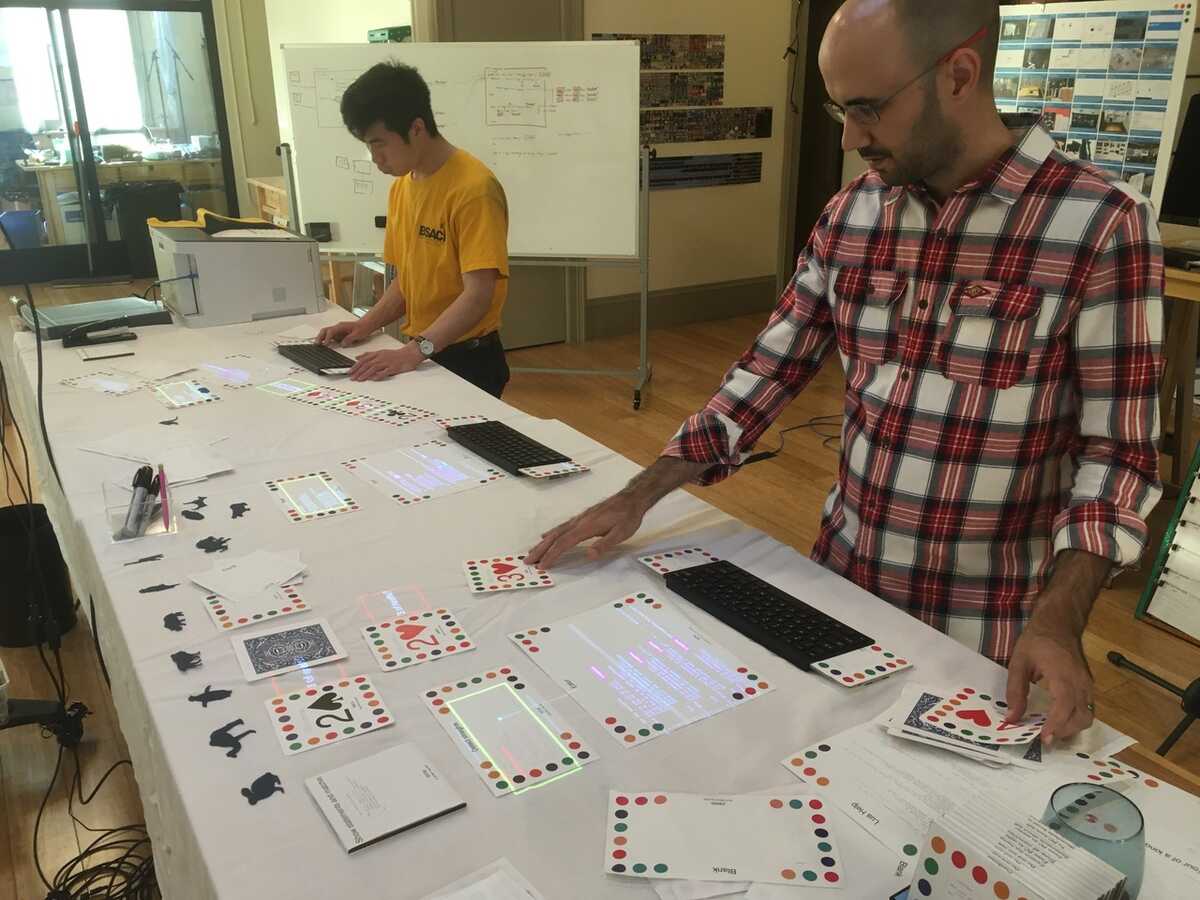

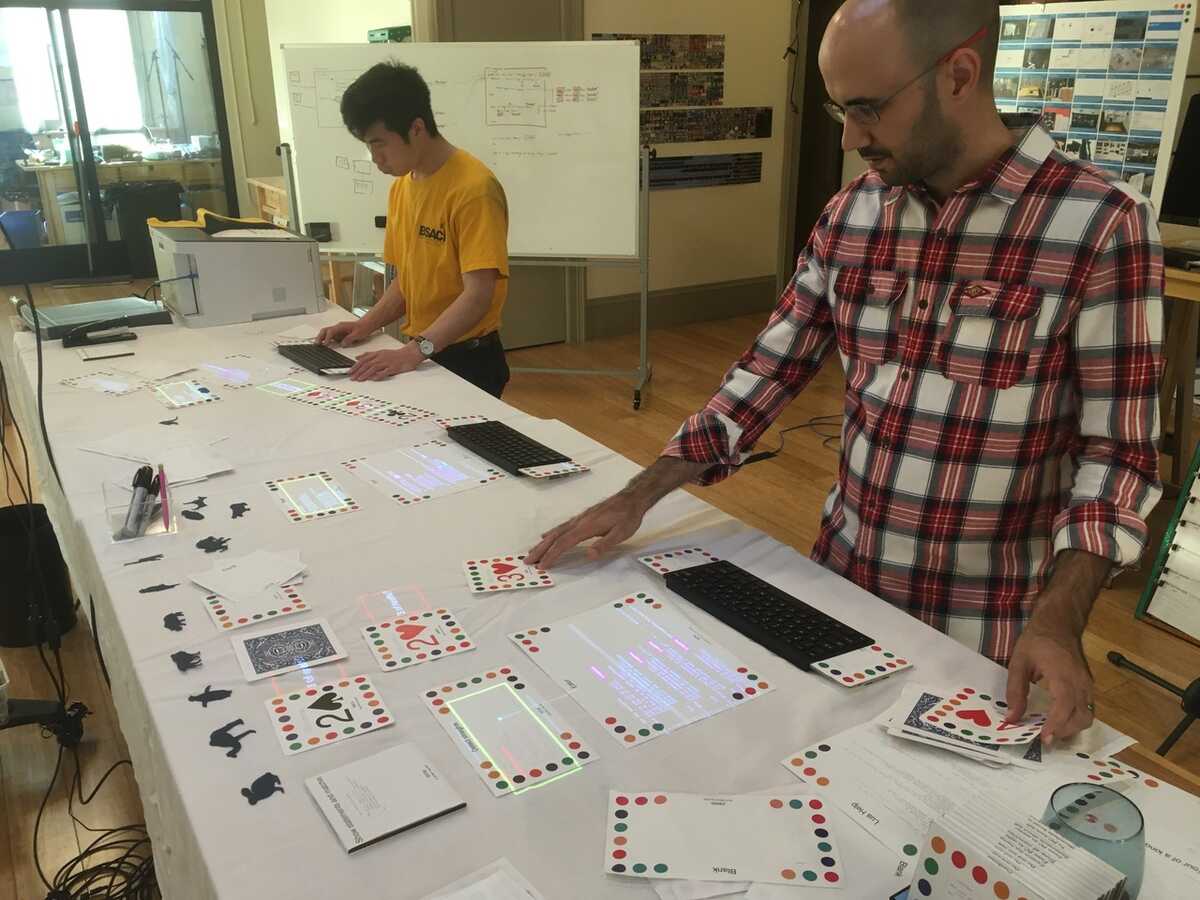

Card games

I brought out a deck of Realtalk playing cards that I had printed on cardstock (all four suits, numbered 2 through 7), and we played some games:

- Detect when a four-of-a-kind is on the table.

- Draw an arrow from red cards to black cards of the same number.

- Draw an arrow from each card to the next card of the same suit.

- Detect a straight (a sequence of ascending cards) and label the head of the straight (e.g "Straight of 5 clubs").

Konlin diverged for a bit and started trying to make a blackjack game.

All matches

I had originally conceived the playing cards in order to introduce "all matches", and we did that now:

- How many cards are on the table? How many of each suit?

- What is the sum of the numbers on the cards?

- etc

I introduced both "With all /matches/" and "When /all xs/", but should have just stuck with the former.

Cards + logic gates

I tried to tie the cards back to the logic gates from last time, to make the point about how Realtalk activities can blend together. I brought out the Clocks they had made, and had them write a rule that would turn every card into a clock, with a duty cycle based on the card number (e.g. a "3" should be active 30% of the time).

Shawn and Konlin did it differently (Shawn's was active 0.3 sec out of 1 sec, and Konlin's was active 1 sec out of 3.3 sec), so I wished for a clock period and they had to respect my wish, along with defaulting to 1 sec when there was no wish.

Final boss

The last challenge of the day was "Ask for straights". When we put a "2" card on the table, there should be a box to its right asking for the "3". When we put down the "3" in that spot, it should ask for the "4", and so on.

When they completed this challenge, it was almost 5 pm and that seemed like a suitable place to stop.

-- first card of the straight

When /p/ is the (2) of /suit/:

Claim (p) wants the next card.

End

-- check if the next card is to the right

When /p/ wants the next card,

/p/ is the /n/ of /suit/,

/p/ points "right" at /p2/,

/p2/ is the /n2/ of /suit/,

n2 == n + 1:

Claim (p) got the next card.

Claim (p2) wants the next card.

End

-- if the next card is not to the right, ask for it

When /p/ wants the next card,

/nobody/ claims /p/ got the next card,

/p/ is the /n/ of /suit/,

/p/ has width /w/, /p/ has height /h/,

/box/ is a new box on the "right" of /p/ with width /w/ height /h/:

Wish (box) is outlined "green" with stroke width (0.02).

local label = string.format("%d of %s?", n+1, suit)

Wish (box) is labelled (label).

End

Reflections

I really liked that we started from an empty space and built the world from scratch. Assembling the Dynalamp head was pretty easy and fun. The mic stand may have been a bit tedious but okay, and running cables and positioning lamps is mostly annoying. (The NUC trouble: keyboards initially weren't working because of a bad USB port. We swapped NUCs, and then keyboards appeared not to be working because F1 had no effect, but that was actually because Realtalk was stuck in calibration mode because F1 had been pressed on some other keyboard no longer attached. We eventually got things working after several NUC swaps and port swaps, but it slowed momentum and was embarrassing.)

My main impression after the first day was that I should have gone way slower. I was excited about my clever agenda that attempted to cover everything in a single day. But even with the visualizers, learning Realtalk is hard. I was introducing things like conditional clauses and default matches before they had a solid understanding of normal clauses and matches, or even what parentheses and slashes mean, and they were getting confused. On day two, I tried to go slowly over the fundamentals again. I think there could be a series of introductory games just about statements, matching, and syntax that goes really slowly and makes the basics extremely visible and tangible and fun.

Introducing memories on day one was a mistake. Memories are a great way of representing state within the Realtalk model of computation. But they're really confusing and distracting if you aren't yet fluent in thinking in that model, and especially if you don't yet understand Realtalky ways of physically arranging objects so as to represent most state physically. And especially if you haven't unlearned your imperative programming habits. I was carried away with wanting to make a latch to complete the logic circuits analogy. We should have just stayed with reactive Realtalk and physical state, and seen how far we can go with just that. Later, at some advanced workshop, I could introduce ticking and convergence, and then histories, and then memories.

Likewise for "When /all xs/". Should have just stuck with "With all /matches/", and then brought up /all xs/ much later as a handy shortcut, once aggregation itself was well understood.

Some topics, like memories, came up a bit earlier than intended because people wanted to make things and I was trying to help them along. Konlin in particular would diverge to make things (e.g. the blackjack game) which needed state, so I gave him the tools to make it. But memories are a power tool, and he really wasn't ready. But also, the power tools were only necessary because he was approaching the game in a non-Realtalky way, and the better lesson would have been to help him redesign the game so it was more in-the-world and didn't need virtual state in the first place. But probably the best response would have been "let's come back to this once we understand Realtalk better". I was trying to avoid being strict or discouraging, but in an introductory workshop, "we haven't learned how to approach this yet" may be better than obliging people in going out of their depth.

I found both of them writing code that mutated external variables, e.g.

sum = 0

When /card/ is the /n/ of /suit/:

sum = sum + n

End

The global declaration should almost certainly be illegal. But even if sum were a local, this code is meaningless and ideally wouldn't be allowed without an "I know what I'm doing" annotation. I think this comes from thinking of When as an imperative "for" loop. There is probably a way of presenting reactivity that avoids this thinking.

There were other assumptions they made about the computational model which surprised me. For example, Konlin was doing things like this, assuming that each page was its own process:

while (true) do

When /p/ is a "page": ... End

sleep(1)

end

Things like this probably aren't a big deal; they're just grasping for techniques that worked in conventional programming, and they just need to unlearn them.

There were a handful of divergences, which were dutifully caught by the divergence catcher. These were all loops of the form:

When /nobody/ claims xyz:

Claim xyz.

End

This would have been less disruptive if Shawn and Konlin were working in separate areas, although it wasn't a big deal and was just kind of a goofy moment when it happened.

I had hoped we would keep an ongoing gallery/journal via a whiteboard of photos and printouts, and it sort of worked, at least on day one, but it wasn't as good as it could have been. We should have ritualistically printed and photographed after every segment, and otherwise been more diligent about documenting. It's hard because you get caught up in the work and don't want to take time out.

I can imagine starting a workshop by giving each person a binder/organizer or personal posterboard, initializing it with cheat sheets etc, and then having everyone add to it as they make things.

Most of the time, each of us was continuously patching a single Blank. It would be more Realtalky to be continuously printing and spreading out many objects. We did what we did mostly because it was the lowest friction, and partly because of limited table space. But having the printer nearby was helpful.

I thought the playing cards were really good! They were distinct, tangible, and familiar objects that felt good to hold and arrange, and had natural relationships among themselves. They suggested a lot of Realtalky challenges. Of course, a Realtalk with recognizers would use actual real-life playing cards, not my dorky small squares.

"Ask for straights" was a good final boss. It was difficult but doable, required thinking in Realtalk and making claims to oneself, assessing a physical situation and having physical objects respond to each other, and it felt fun to place down cards and see the reaction.

Both Shawn and Konlin had positive things to say after day one. Konlin said that it may have been his favorite workshop he's ever been to.

Pictures

starting from an empty space

building Dynalamp heads

building Dynalamp stands

setting up Dynalamps

making tools

matching statements

logic gates

whiteboard at end of day one

lecture on day two

matching, day two

a straight of 4 spades

blackjack

final boss

video of Shawn and Konlin explaining their solution to the final boss