I keep thinking about this video from 1972 where Bob Kahn performs a live animation to explain the structure of the arpanet

—Bret Victor

Making Dreams Real

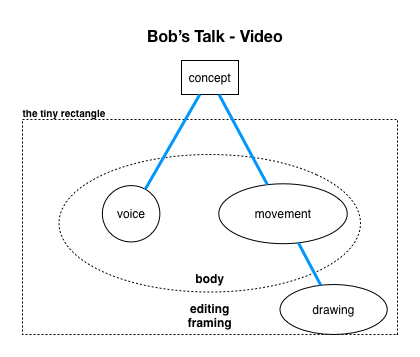

It occurred to me that there are actually three people in this video but only one—Bob—is seen. The other two—the cameraman and the editor—leave their mark via camera moves and cutaways, respectively. For example, the camera moves to focus on particular parts of the blackboard and the editor occasionally cuts away to provide “footnote” information like the insert shot of the first generation IMP. These two cinematic tricks are powerful and a big part of "movie magic” and why thy are so easily digestible.

As in dreams, what seems logical in the moment (Bob Kahn vanished and in his place stands an IMP) would be incomprehensible or even terrifying in the physical world ("Someone help! Bob has been crushed by an IMP! Oh, the tragedy!”). Dynamic Media for Dynamic Thinking require a new alchemy: the engagement of magic with the ability to actively explore the data (unlike traditional magic/cinema/"story thinking", which prize engagement above all else).

How can the virtual/magical aspects of cinematic magic be made less ephemeral and more physical? “Physical zoom,” for example, could be achieved by walking closer to the blackboard to see what Bob is writing. But how might the power of a cut between two shots be manifested in the physical world?

(In an argument against the cut, consider Iñárritu, Cuaron, and Malick’s recent collaborations with cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki—Children of Men, Tree of Life, Gravity, Birdman, the Revenant—where single takes “tell the story” in a more “realistic manner” instead of the convention of stitching together short shots to create the illusion of continuity. Unfortunately, many of the examples’ violence are the sole reason these films are hyped as “realistic.”)

Exploring By Copying

A while back, I had the idea to “cover" a talk (like a band doing a cover song). This idea came from a misunderstanding I had about Bret’s Future of Programming talk before I’d seen it. I incorrectly understood that he had taken an existing Alan Kay talk, memorized it verbatim, and re-presented it exactly the same 30 years later. [Tangential inspiration aside, it should be noted that I love Bret’s talk.]

Combining this inspiration with my frustration with the current generation of presentation tools and the fact that Bob Kahn was a somewhat regular houseguest in my childhood, I made a “cover song” of Bob’s explanation…

(Also, here are the two videos separately: Original | Conned Kahn.)

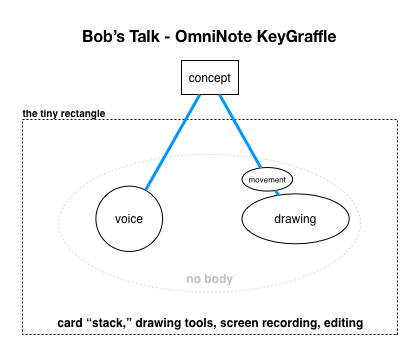

I approached making this video as how one might paint a copy of a master’s work in a museum, trying to emulate every detail as precisely as possible. A big thanks to RMO and Max Hawkins for Gentle/Drift, which allowed me to practice the microtonal/rhythmic variations of Bob’s speech. OmniGraffle was my drawing tool of choice, and in almost every case, Bob’s blackboard drawing was more efficient (even when I was copying and pasting shapes instead of drawing them, it was hard to keep up). As Bret pointed out, the hardest parts to emulate in OmniGraffle were when Bob used both hands.

Embodied Explanation

It’s kind of mind-blowing. What has gone wrong such that a guy with a piece of chalk and an eraser can knock the pants off of Keynote. Even Ken Perlin's cyber-chalk isn't near this level of improvisational fluidity and expressiveness, let alone... omg, is Bob pointing to his diagram with his hands? Is he pointing to two things at once? what sorcery is this

—Bret Victor

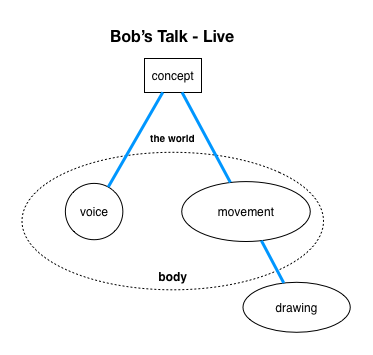

Copying Bob’s talk forced me to look at it quite closely. There’s more to it than two hands and cinematic magic. It’s a dynamic process—a dance that transitions effortlessly back and forth between voice and drawing, idea and body, concept to physical, invisible to visible. If someone had interrupted Bob mid-explanation with a question, he could have adapted in real time. Not so with today's presentation software: a questioning/exploring audience would inevitably endure some painful downtime watching the presenter figuring out the software, discouraging further group exploration. How can we not do better than this?

One senses that Bob didn’t rehearse much other than to prepare a loose script and make five rectangles on the board. He knows his subject and he knows how to draw basic lines and shapes. That’s all he needed.

In my cover version (especially when watched alone), it’s hard to ignore that you’re watching someone using a computer in an attempt to illustrate concepts instead of directly illustrating those concepts. Today’s computer interfaces funnel all body energy to a single finger on the pointing device (I had to practice the smooth circular gestures Bob makes as he waves his hand around the loop network). Despite my competency with OmniGraffle (read: lots of unembodied hours learning keyboard shortcuts), I had to practice to make it seem natural and keep pace with Bob. Perhaps sketching with an iPad Pro would have gotten me closer?

It occurs to me that so many instructional videos, when created with or inspired by modern presentation software, are disembodied visual explanations. Compare the methods used by these two videos about how the Internet works: this fancy yet hollow Powerpoint-esque video (5m37s—only need to watch a minute or so) versus this "made by hand” video (4m48s). I imagine that the former was mostly made by people sitting down in front of tiny rectangles; the latter was a fun and physical project with just a few quick edits added in software at the end.

It seems worth adding “give Bob’s talk" to the list of achievable goals for the system by year’s end.