Hey all, this is an email about a little prototype I made. There's a lot of context around the prototype, so please excuse the lengthy email.

A few days ago, Nagle forwarded me an email from John Maloney explaining how John was going to work with children at Parts & Crafts for a few weeks as a test of GP. As a start, he mentioned making a program like this:

I wrote a response back wondering a) would this be interesting for kids? (the most important piece) and b) would children understand what the program was doing and be able to make it themselves? In the email I wrote a breakdown of some of the ideas that were implied in this program but not shown, things like what the "pixels" block referred to, what the value <v> meant, etc.

From the responses I got from John and Mark Guzdial (John's collaborator), I felt like they didn't really see what I was getting at or why I thought it was important. This made me simultaneously despondent and also more motivated to show them what I meant.

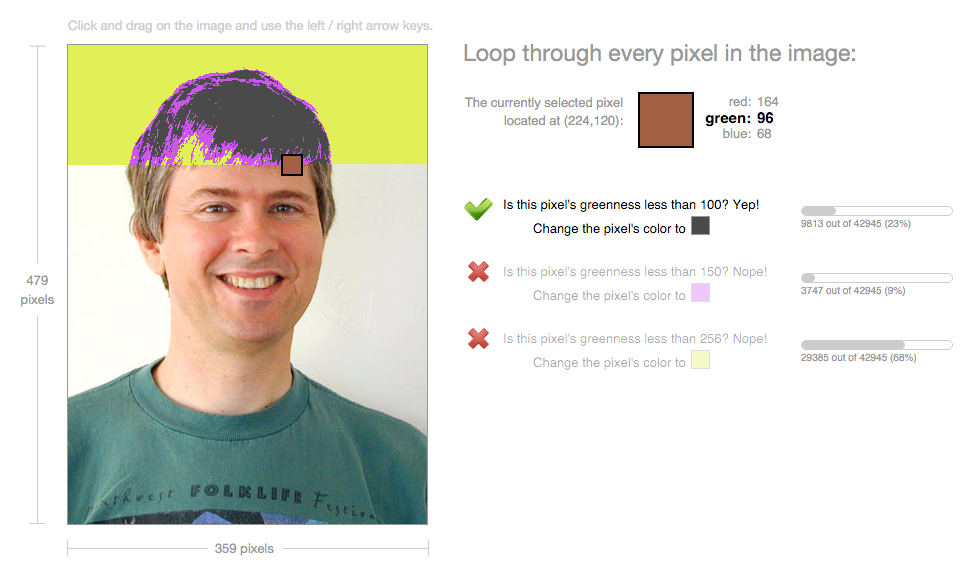

As a design exercise, I decided to mock up and code a little prototype of what I thought a more understandable representation of that program might be. I ignored how a person would actually create this program and focused on just conveying what it did. Here it is:

There's a lot of stuff that's probably not so great about this sketch (I was pretty lazy in making it), but it seemed like John and Mark both had immediate turnarounds from their previous lukewarm responses and really liked it. I made the claim that whatever programming environments we have should strive toward this ideal of understandability, and I think that resonated with both of them after they saw the prototype.

A couple things naive things I noticed when making and using this: computers are fast. Somehow I felt like I never quite realized that the computer blows through almost 200,000 pixels in no time. Arrowing through the picture at even at 20 pixels per frame still feels incredibly slow as the cursor scans through the lines. It made me wonder why computers are ever slow, which I know abstractly but have never felt as viscerally as I did with this mockup.

I also found it pretty weird that the white pixels in the background are somehow "greener" than John's green shirt. RGB values are weird!

Anyway, what's interesting is that the day after I sent this mockup to the email thread with John, Nagle showed the prototype to three children at Parts & Crafts and it went really well. I'm going to paste the entire contents of Nagle's observations of that session because I think they're absolutely wonderful and connect the use of the prototype with a larger emotional/developmental context.

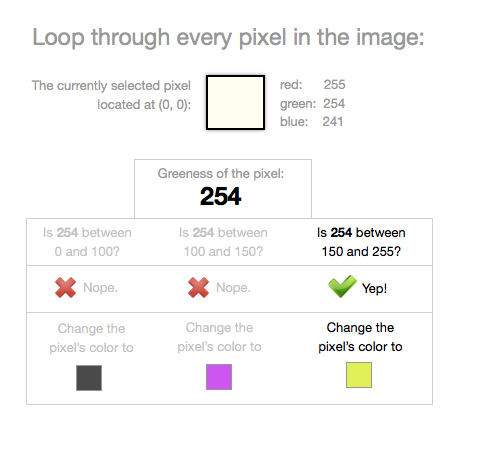

But before I paste Nagle's wonderful email, I'd just like to show an alternative mockup of the if-statement in that program. While I was designing I was worried about how understandable the if-statement was, and Nagle confirmed that the children had some questions about it. I thought this might be a little clearer:

(I didn't include the statistics about "pixels so far" in this mockup because I was lazy. They should still be there, I think.)

Anyway, I'll let Nagle's email close out my thoughts on this:

So at the beginning of John and Alisha's class, I invited in an older girl (maybe 10 or 11) after John mentioned he'd like to have more girls in his class at Parts and Crafts. She (Ravenna) is someone who is quite thoughtful and focused, but tends to do only 'crafty' things at P&C (cooking, knitting,) and very explicitly said 'I don't program, and I haven't used scratch before.' I said I would just hang out with her and we'd see.We invited a friend of hers, Harlan (boy, ~9) in. Harlan is very interesting to me in P&C's current batch of kids because he drives the staff crazy. He tends to get lost in his own world and disrupt classes. He's a very nice and friendly kid, but sometimes he just decides that he's going to be a hunchback, pulls his shirt over his head, and proceeds to insist on interacting with everyone as if there is no other reality, and there's no talking him down from it. As an example.Harlan also said that he had never done Scratch before and was convinced he would fail at programming, but he was very cheery in this self-assessment. Will Macfarlane (one of P&C's leads) and I have talked about children who start to 'own' failure and will proudly announce how bad they are at homework, test-taking, etc., perhaps as an unconscious defense-mechanism against the messages their schooling is giving them.So Ravenna and Harlan came, and we started looking at the Marilyn Monroe example. It turns out this was intended for next week, but there was chaos in the classroom with finding a lost projector and getting GP installed on Linux, and I feel like when you offer invitations to an activity that's on trust (trusting me as a human,) and not natural-grown confidence, you have to strike while the iron's hot. So we got out my laptop, and flipped through John's email.It became clear to me in a flash that the GP blocks weren't going to mean anything to these two new-to-blocks kids. So I pulled out Glen's explorable explanation.This was basically great. Really, it provided a substrate for us to talk through what they were seeing happen. As is often the great challenge with teaching, it's to see what somebody else does and doesn't see, and somehow suspend one's own filter of seeing in that process. So the kids start playing around with it, holding the right arrow key. We're joined by a 3rd child, William, who has a lot of Scratch experience, but is less socially mature than the other two. He proceeds to insist on holding the right arrow key. Clearly, it is fun to hold it down.I can't remember the exact flow, but first we talk through the explanation. We look at if the idea of a color in terms of three colors makes sense. At some point, someone asks 'can there ever be all 3 X's?' I think this question is fantastic for a number of reasons. One: it kind of looks like it! We're flipping through quickly. The X's and Check's clearly have a kind of raw, basic, iconic appeal. Somehow one of the kids is using that, perhaps unconsciously, as a visual anchor. It also gets at the underlying logical structure here. It's important to me that the question was: can they ever all be X's -- maybe it is visually clearer that things don't ever go all Check, but as you race through the example, X's blur together and it's a genuine question.So, they started investigating this. Harlan proposed that it is true that there is always exactly one checkmark, and they proceeded to confirm this. For me this is interesting because part of P&C's frustrations with Harlan is that he never seems to be constructively engaged, and here he is, constructively engaged. To me that means something. We keep looking, and I think then look at the if statements -- how is it that we end up with yellow, magenta, and black, based on the green value.The other interesting thing: the boy William, at some point, exclaimed his realization that the code was testing for 'greenness.' This is very interesting to me, since he had blocks experience, and yet for him too I think the question of '3 X's' was clearly engaging, and it became apparent that this code was initially testing greenness in the conditionals wasn't clear to him.At this point John started doing a group demo, and we watched. I think Ravenna understood this color-to-number decomposition (and I was glad we did that before the group demo, as the class is mostly eager young boys who, as John and I discussed, could be 'overconfident') and there was clearly some transfer. After the demo, we didn't really have enough time to code something. I spent a while trying to get a grumpy cat image to be a png, which took more time than I wanted and our GP crashed on trying to duplicate a block (I think a 'let' block) but it was clear as we built the first 'if block' that Ravenna was following along. We got a first conditional to work on changing colors in the png, but then we ran out of time.The other interesting thing about this story is Ravenna was perpetually convinced that she wasn't understanding what was going on. This was really interesting to me, since she was carrying on a conversation with me with no trouble about what the algorithm was doing, and clearly getting it. So somehow this conversation which served to me as evidence of learning didn't work for her. I assume this is because she didn't get to snap the blocks together herself -- my goal was to snap something together and then hand it over but we ran out of time -- and there's perhaps cultural affect of nerdy young boys doing Scratch which doesn't map on to her own self-image. She also only has an iPad at home, but I think no computer, and I have to imagine this is huge -- she was interested in doing it at home. I'm going to suggest P&C do some 1-on-1 work with her and we'll see.Harlan got spacier by the last 20 or 30 minutes, but that he was engaged for so long up to that point was awesome to me. Having a constructive step for him is I think meaningful in his time at P&C. I think part of the hook for him was that images and manipulating them has a real kind of Instagram-like power to it. It feels real. One of my internal heuristics is 'kids like power,' and maybe this is modified to 'Teens like social power.' One of the theories with Harlan is that he is hitting an early adolescence at 9 and this is why he is socially out of sync with his peers. In the same way -- it seemed to me like he had more of a relationship to this class that was 'this feels real!', as opposed to being able to play with an abstract system solely for the joy of it like some of the other kids. (He is very interested in his digital camera right now, and perhaps prompted by John's demo -- where he zoomed in on a picture (I'm remembering that right?) -- Harlan proceeded to zoom way in on a picture and his camera and point out the pixels.)Ok. That is all! We'll see what happens next week!

Apparently John might try to use my prototype in his class next week, so I may write back to this thread with any observations there. I think I'm also going to send an email out to CDG-All about this because I feel like parts of it cut across our entire organization.