List of 30-second pitches preceding the Codex Hackathon:

Shelfie, start-up with an A.P.I. for retrieving I.S.B.N.’s and eBooks from photographs of book shelves; D.P.L.A., offering a book metadata A.P.I.; Submittable, a one-stop submission services corporation; HarperCollins, “your talent, our authors… I live to serve them”; Sony D.A.D.C., whose spokesperson couldn’t believe what he was saying, which was, “Realistically, you’re going to want D.R.M.”; DropBox, offering 1TB “for life” to the best app developed that made use of their A.P.I.; Project Gitenberg, with whose git-backed books one could, for example, “calculate a reading score”; KickStarter; CloudStitch, for all your spreadsheet-powered website needs; WattPad, a timesuck extraordinaire boasting 24 hours of reading material uploaded every minute, a new user every second, and other “crazy” growth stats (“Interested in changing the face of storytelling as we know it? Cool, us too!”); GitBook; bookmaker; MailChimp, proudly sending 600 million e-mails every day and hawking four Apple-brand wrist watches to the team that made best use of their A.P.I.; wedges, a jQuery widget clearinghouse with a new cross-platform emoji picker; Readium, an open eReader software platform; and Poetica.

After the pitches, someone directed audience members to “dive into your computers.” And that they did.

I went to Codex at the suggestion of Cassandra Xia, who forwarded the mailing list posting. The registration form opened with a pandering call for all the creativity that could fit in a small <input> box:

For example, instead of Mister Robert Ochshorn, I could have been Mystery Robert Ochshorn. Hell, I could have written a short novel right there. I filled out the form in my finest straight-edge deadpan.

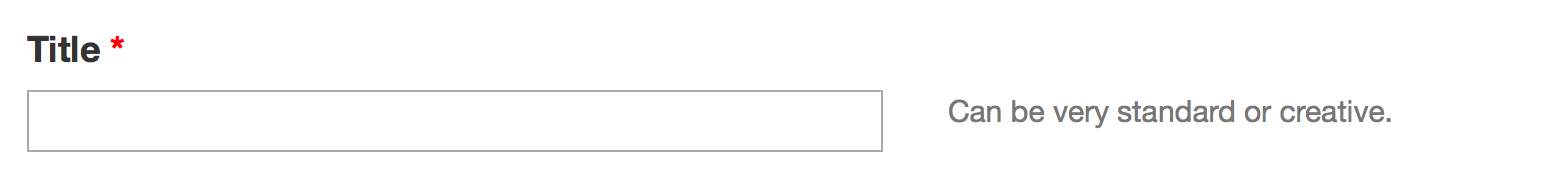

Coincidentally, I had been communicating with Dalida Maria Benfield about making a digital-physical codex for an upcoming exhibition, so I invited her to join for the event. Our conversation eventually swerved and weaved to include Dany Qumsiyeh, Matthew Battles, SJ Klein, and others (all in CC). We carved out a corner of the space with Noisebridge’s DIY Book Scanner and started leafing through the Code for America bookshelf. After a trip to TAP Plastics, we had an annotation workflow all worked out:

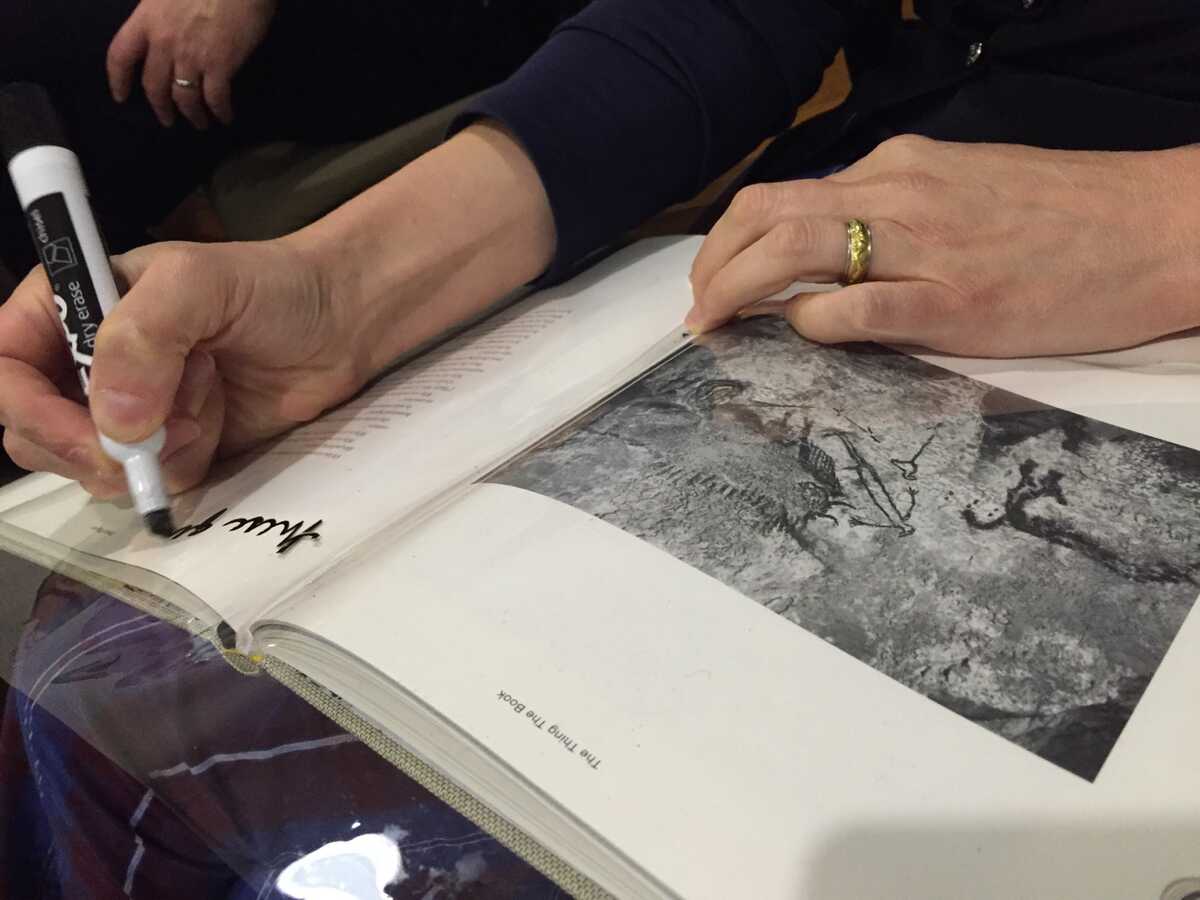

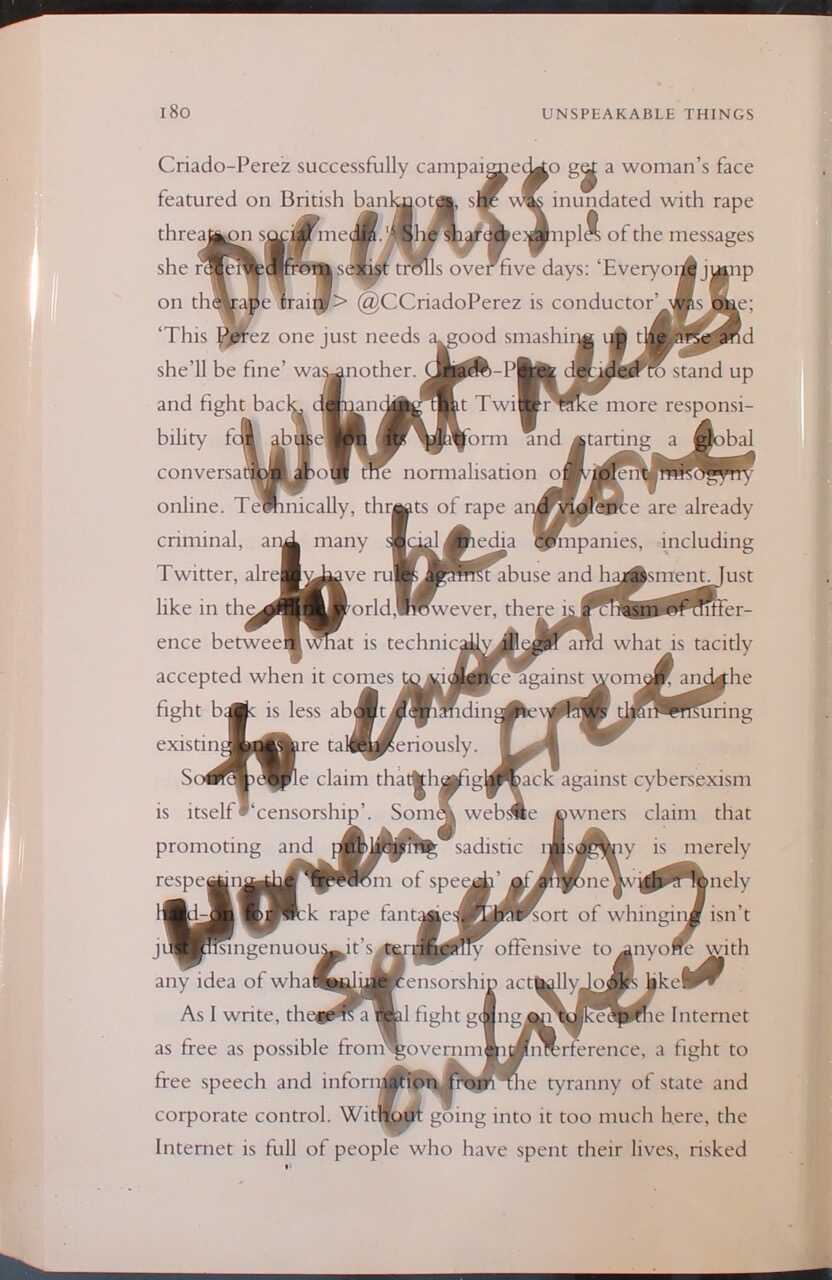

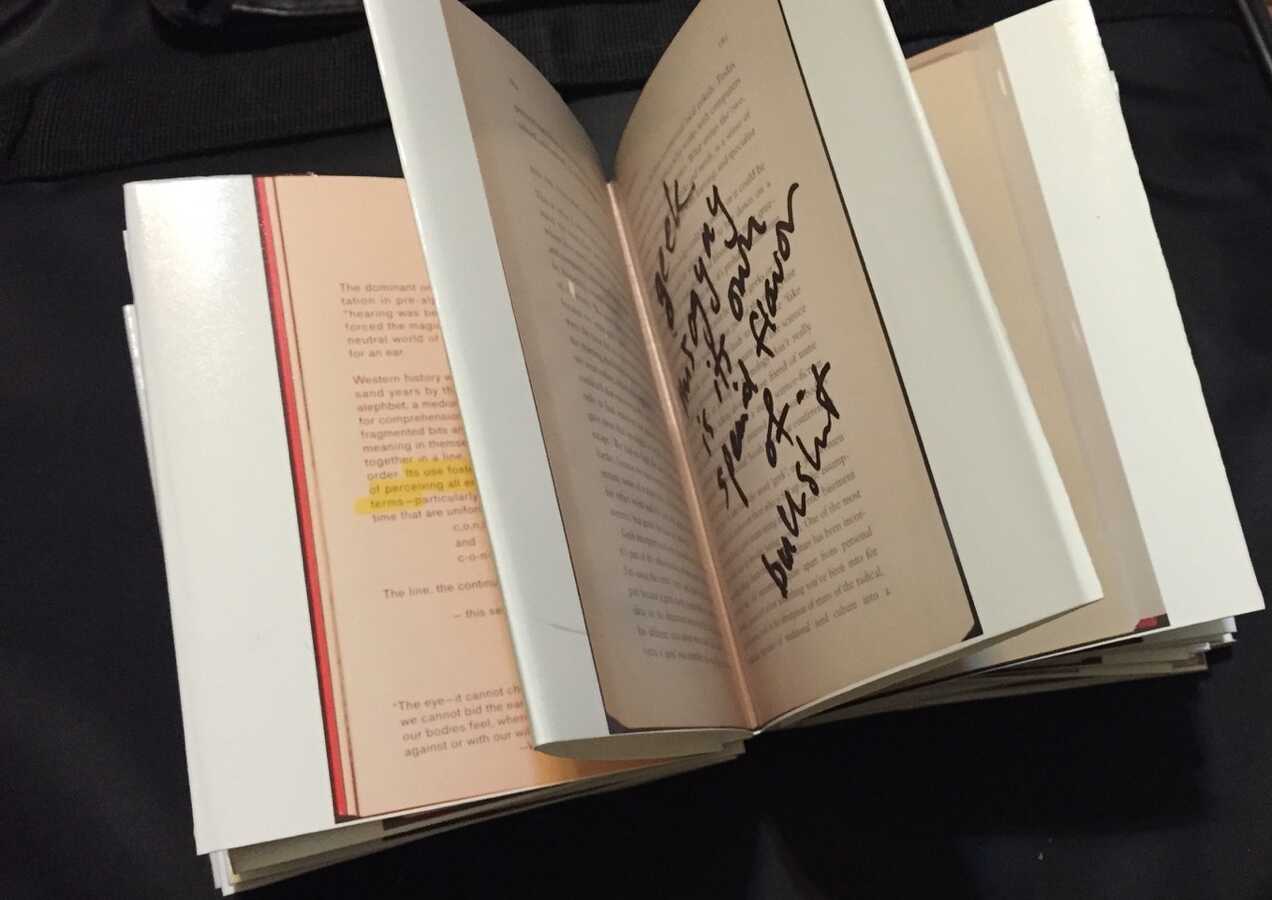

With a protective layer of thin acrylic and dry-erase markers, we could fluidly mark up the surface of any book, and then scan it to create a pristine digital copy:

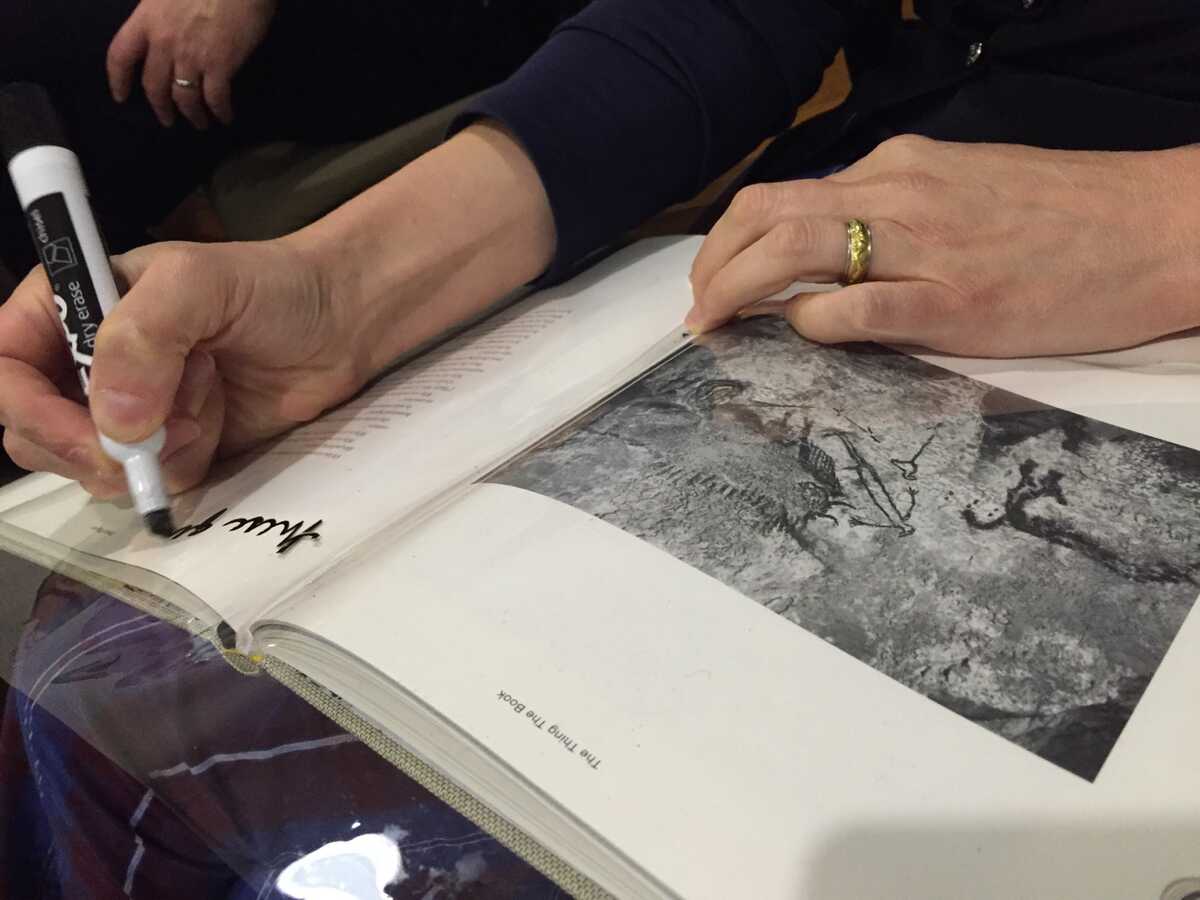

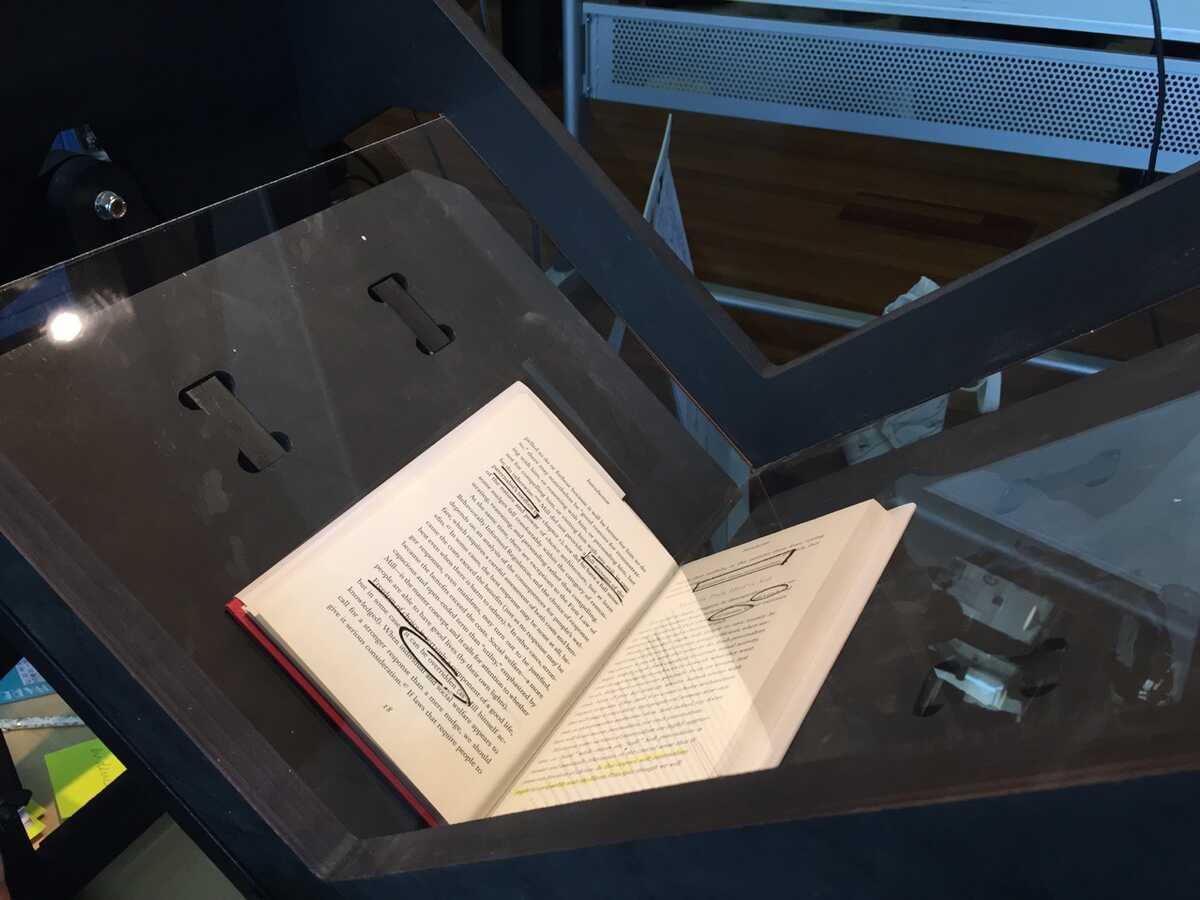

The scans came out clean and crisp, with only the subtle hints of gloss:

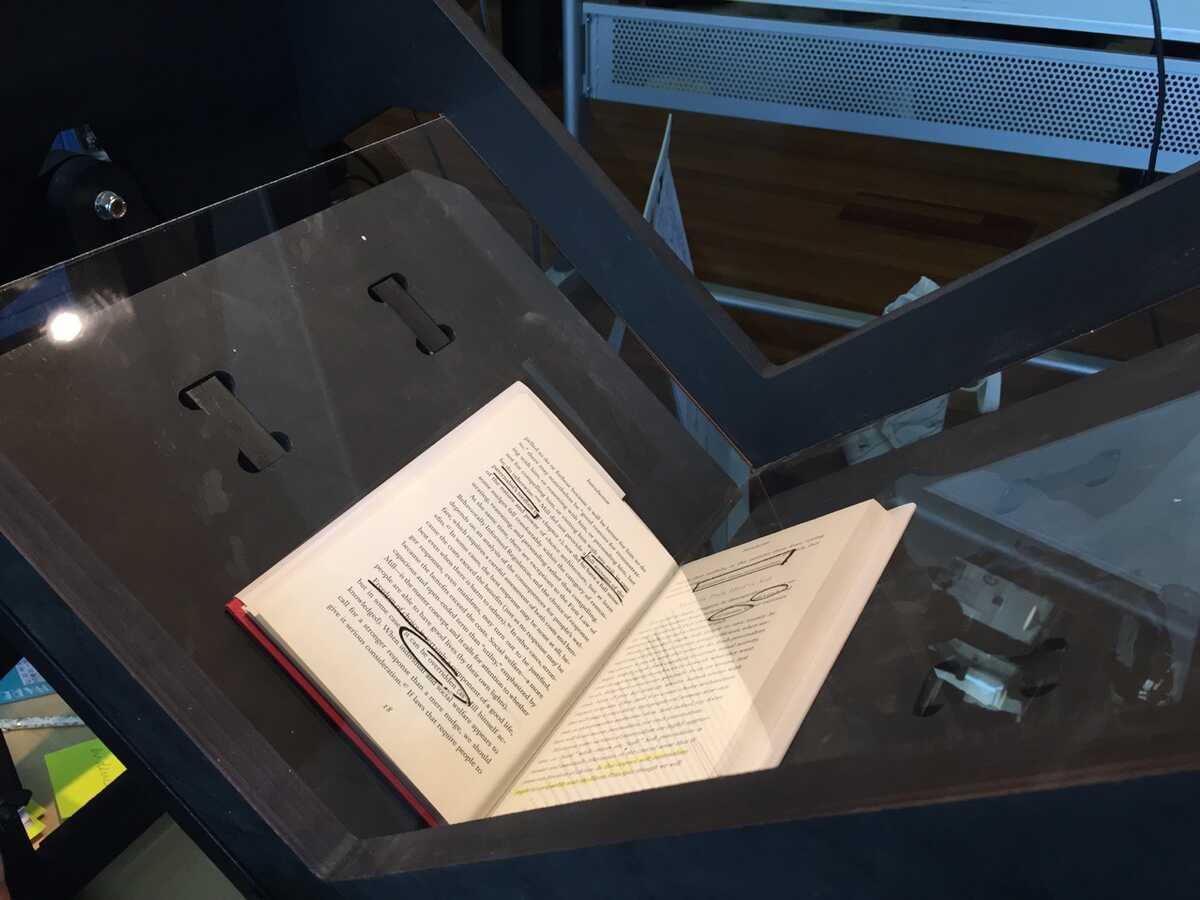

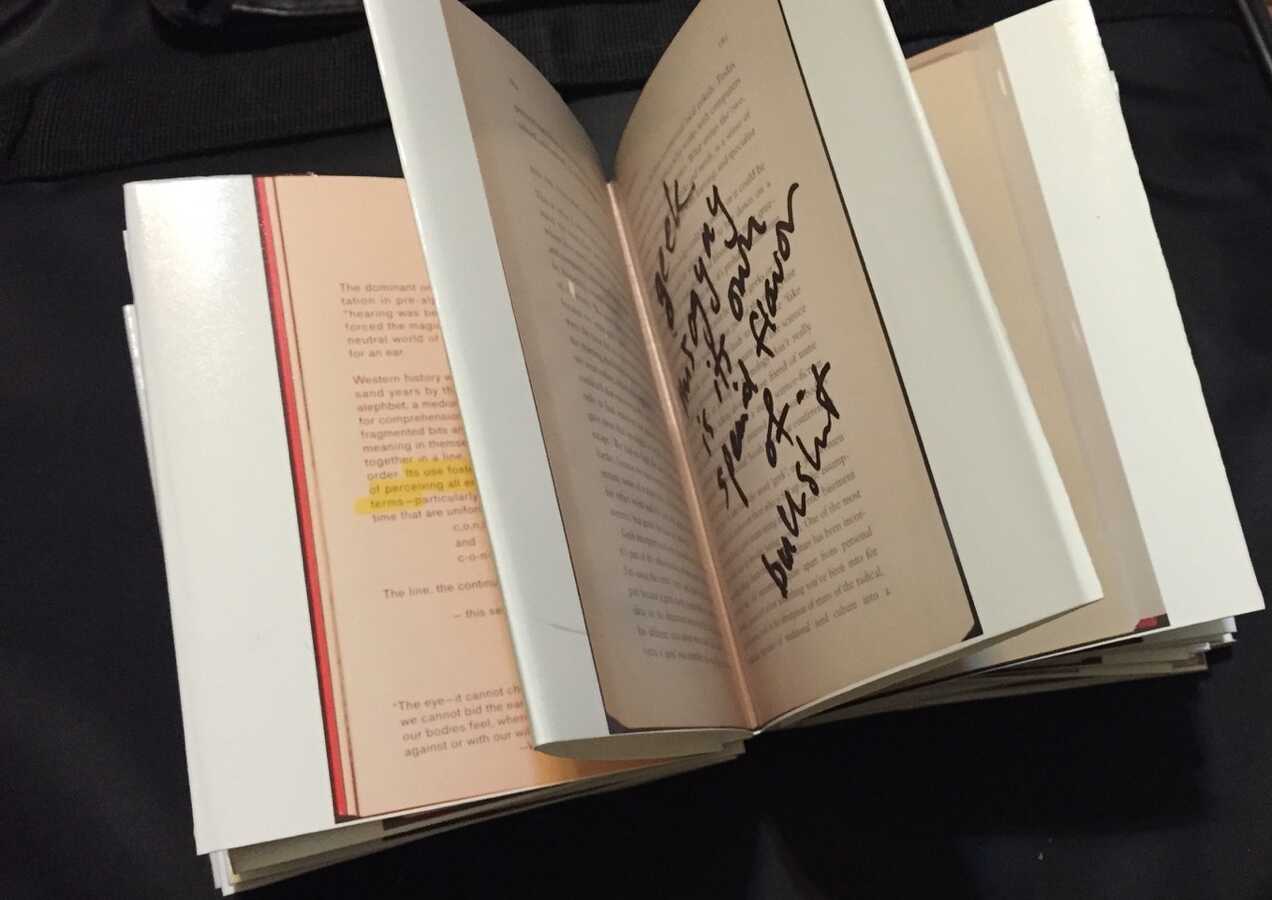

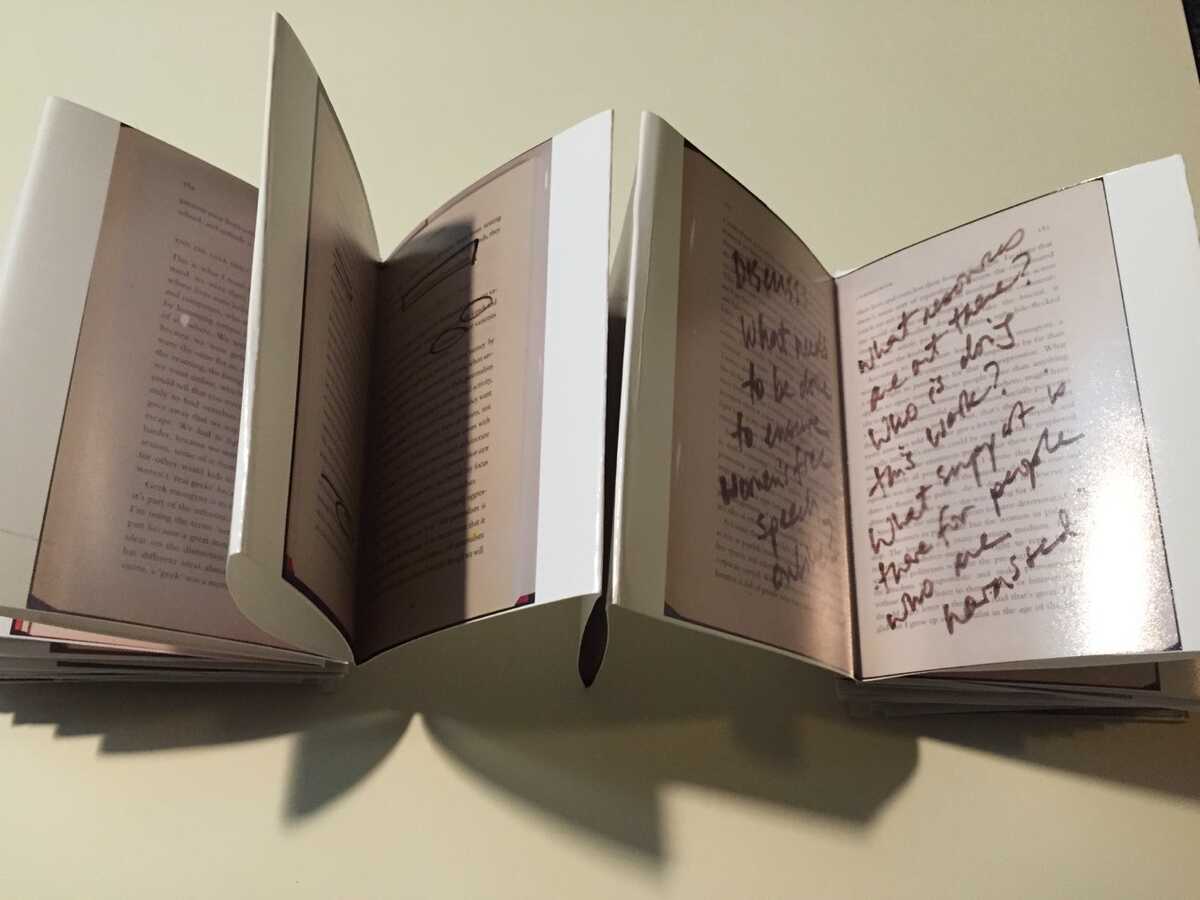

Some of the commentary was written on the book, and some was discussed orally around it. Here, pictured, we assembled a rag-tag crew of beleaguered intelligentsia for a discussion about one particularly provocative spread (asking—not answering—a suite of questions about an early cave painting):

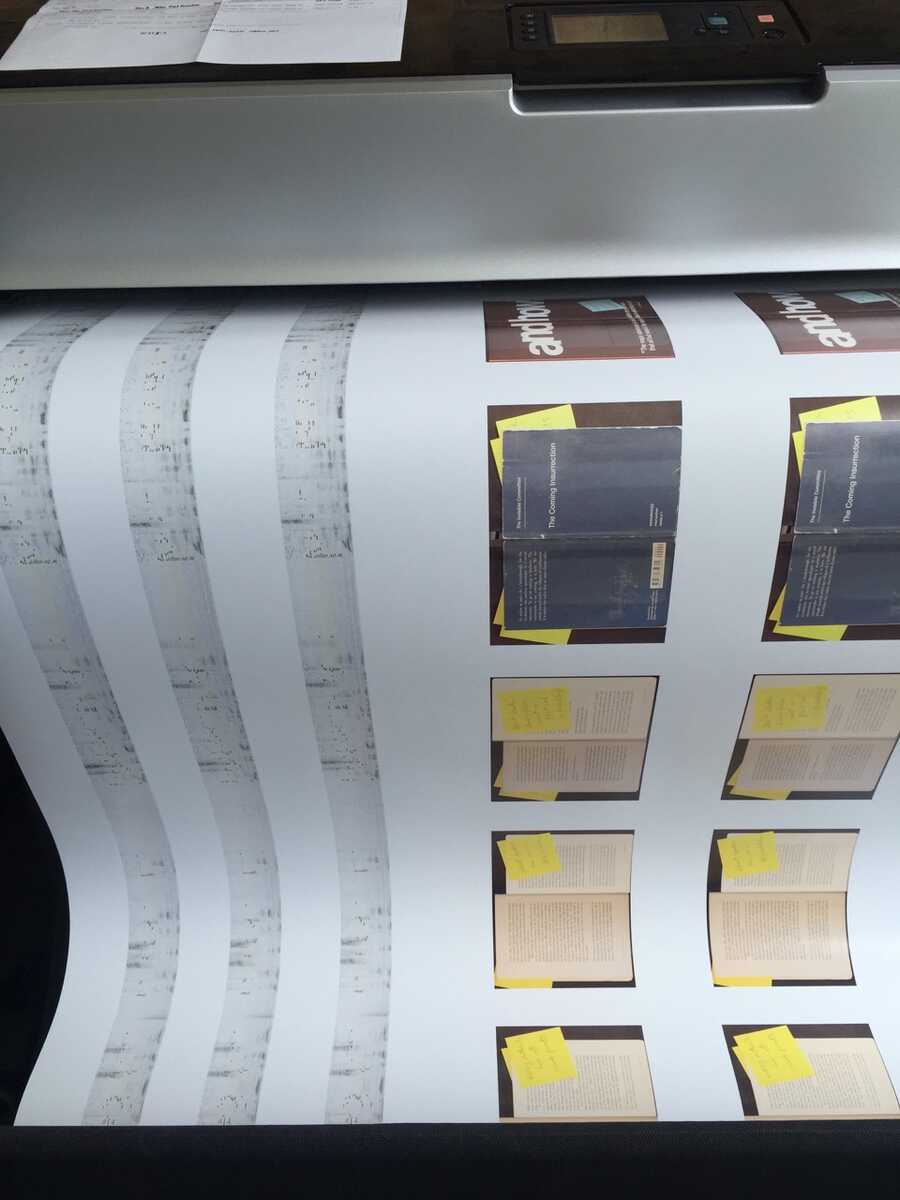

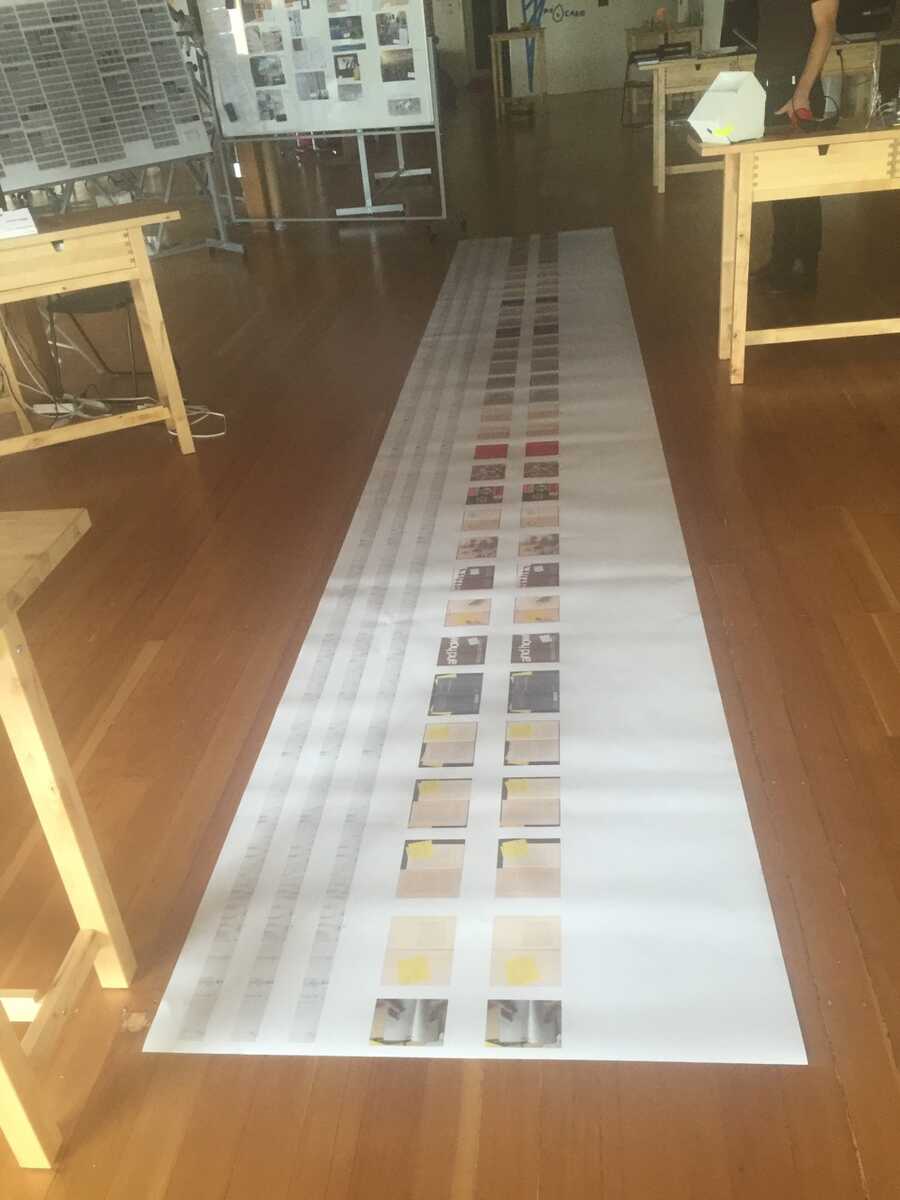

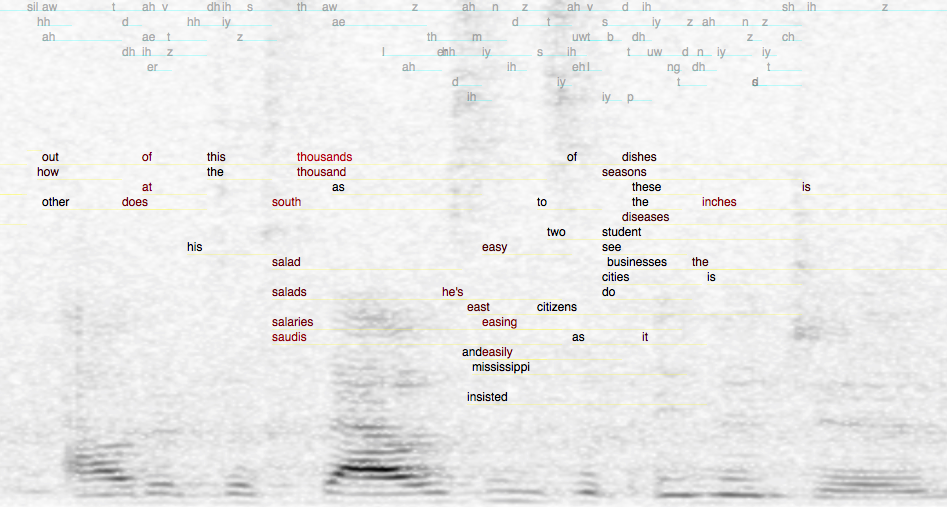

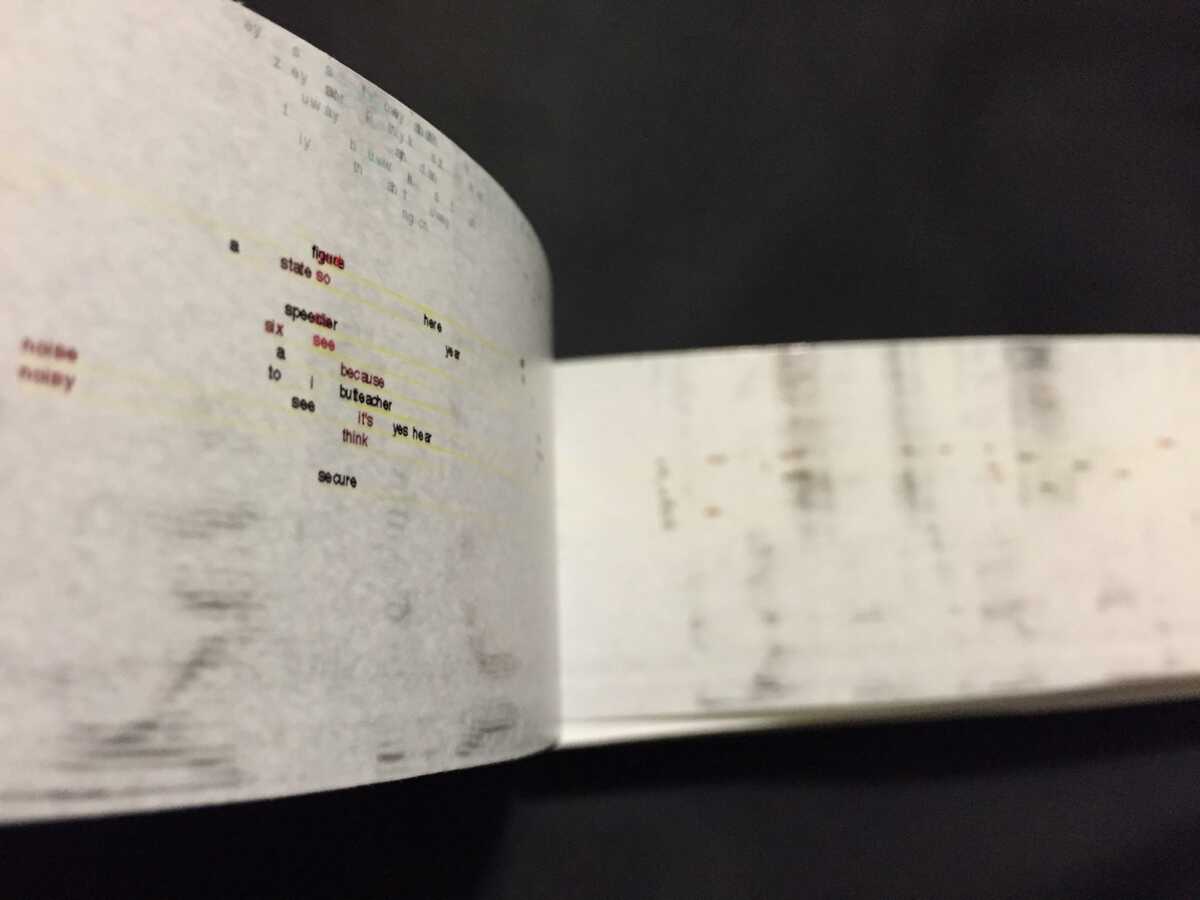

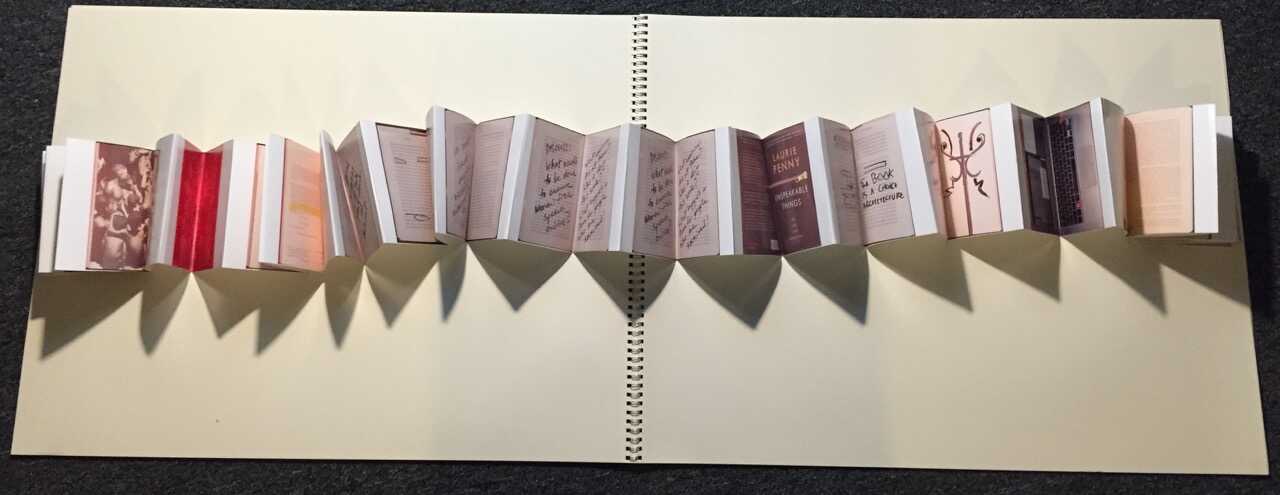

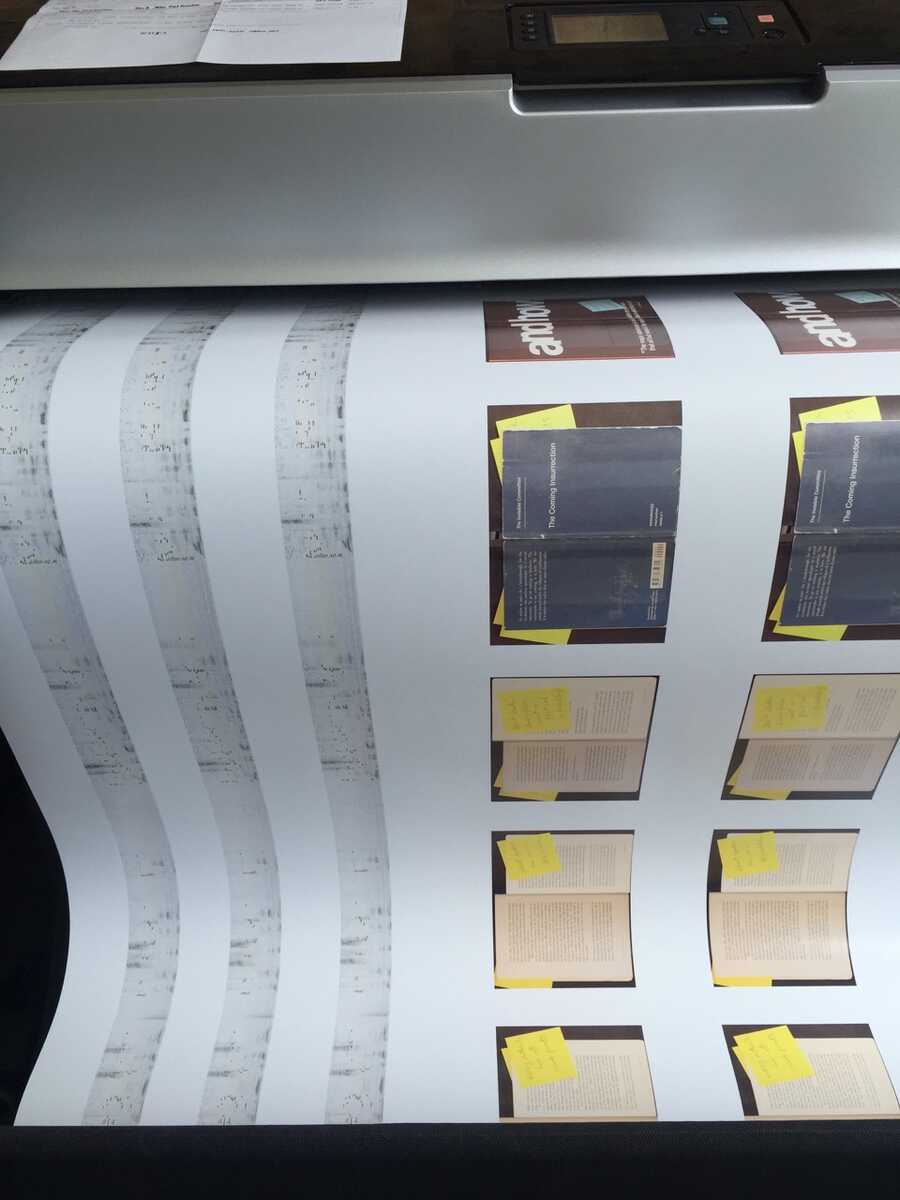

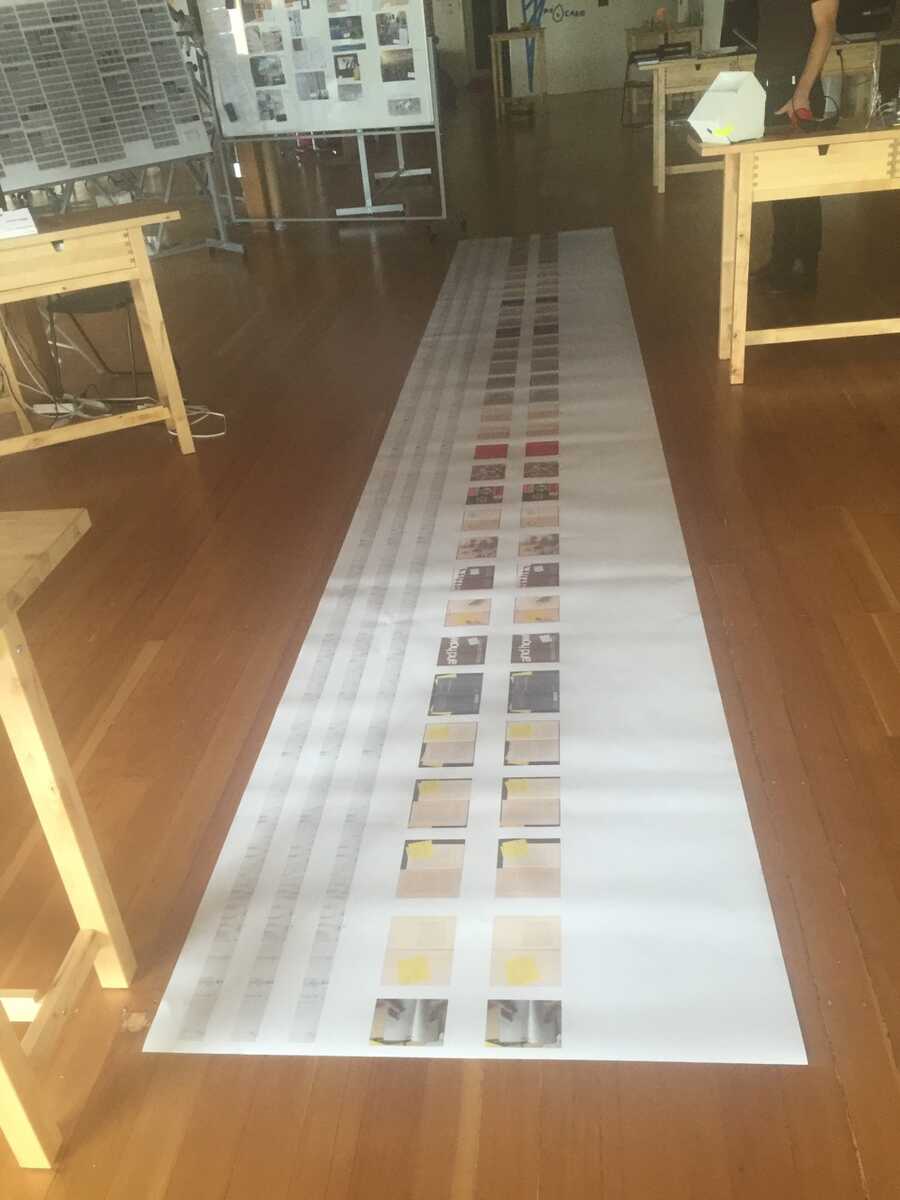

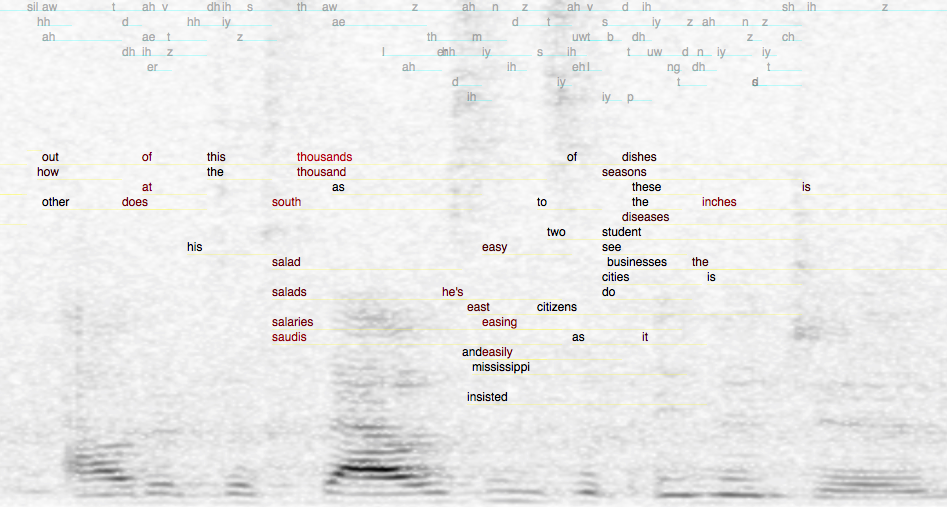

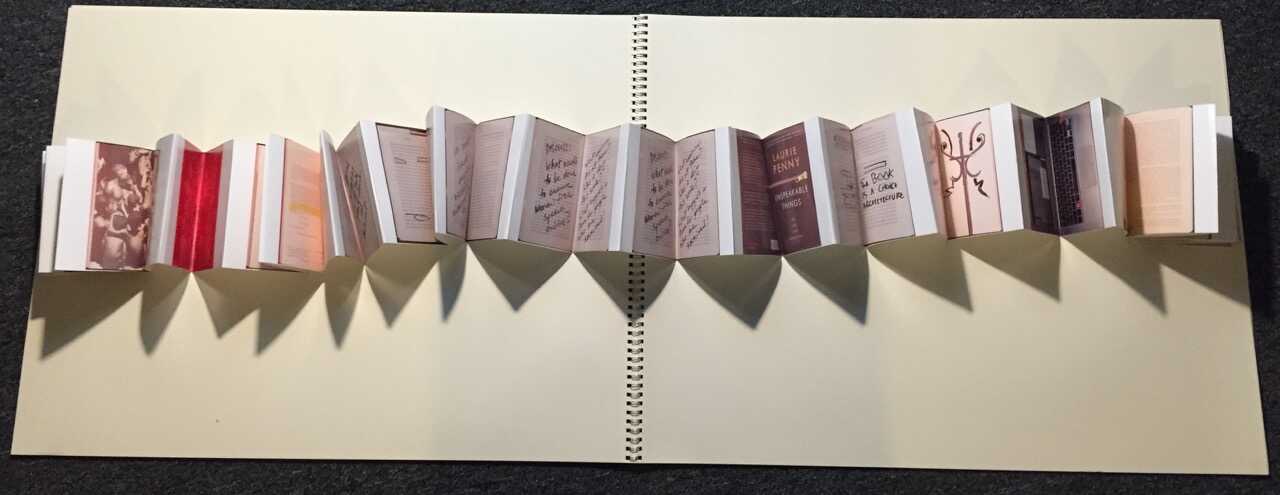

On Sunday morning—after marking/scanning some 60 pages and recording some 30 or 40 minutes of conversation—we assembled all of the scans, and spectrally-phonetically rendered out 15 minutes of conversation for printing at CDG:

Dalida and Matthew embarked on the epic cutting task (more on this later) while I threw together a quick-n-dirty web version (to be hosted on the venerable lowerquality.com domain) video-book annotation on top of some of the annotated McLuhan (click on the 2nd, 3rd, or 5th spread).

In true hackathon form, we made it back to the Code for America HQ with our cut codices just as the first few demos were underway. Some Google VR/ML gurus brought “the dream” of surrealist neural nets into the library consciousness; one group promised with an icy innocence “to take the icky out of the anonymous Internet” by making a community reading platform for children where their input fields were constrained to child-friendly emoji instead of the full vulgar range of UTF-8; the M.C. for the demos collaborated on a crowd-sourced app for condensing literature from 0-100% percent of its original length (our host conceded that it was not a serious suggestion for literature, but quickly asserted a somber value for other texts, like government documents); frictionless eBook purchasing by using all of the A.P.I.s; git-backed “forking” to establish the law and order regime of Version Control over slippery recipes; &c &c &c.

One moment from the demos that stuck with me was the presentation of “Kindlr,” by the Shelfie team, which they promised would launch in Canada soon. Their idea was to make a dating app based on literary holdings and interests (here’s looking at your new bookshelf, Glen). By leveraging Shelfie’s trademark computer vision spine recognition technology, the idea went, users looking for love could be effortlessly onboarded into totally-not-awkward dates with plenty to talk about. If all else failed, you could read together. “In bed.” Speaking of awkward moments, that was definitely one of them. The front-end engineer slipped the line out apologetically, and it was painful for the whole room, but I felt there might be a germ of some deep truth lurking there. Books are intimate objects, solitary or romantic, and what pains the public schools must go through to dull them into pedagogy (reading comprehension tests: “can be very standard or creative”). I think part of the intimacy of books comes from their stillness, which curriculum disrupt by rushing the pages through time, and which general purpose computing tablets dilute with the dull of batteries and the pull of push notifications.

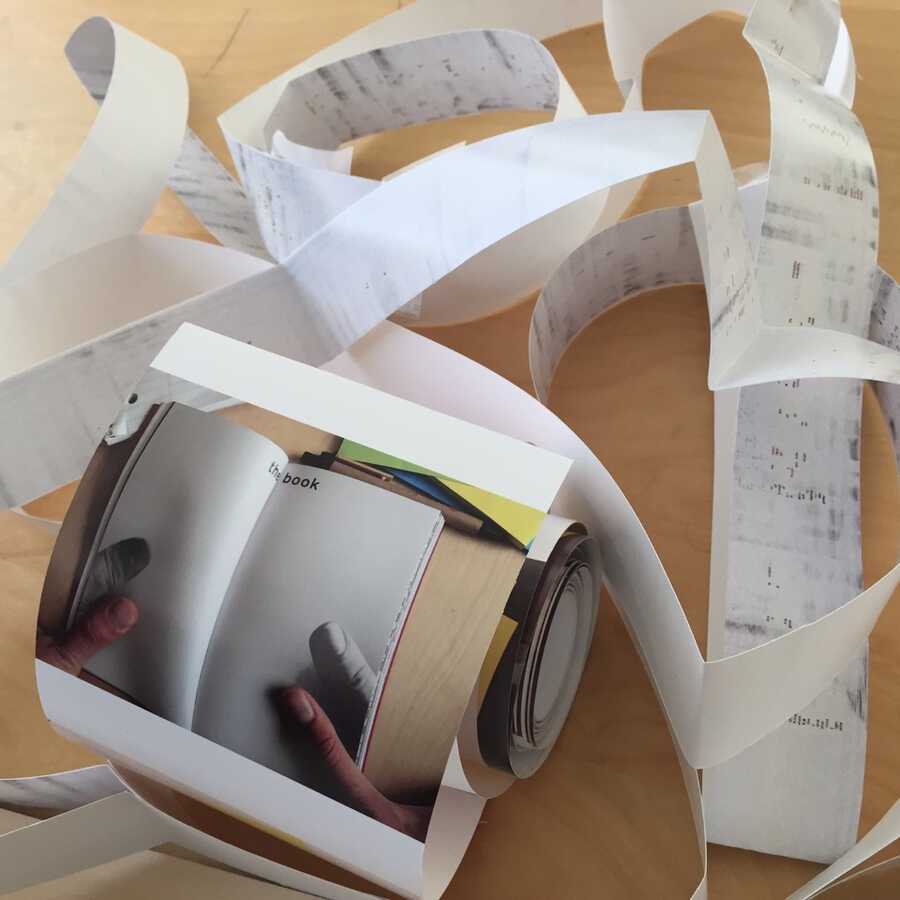

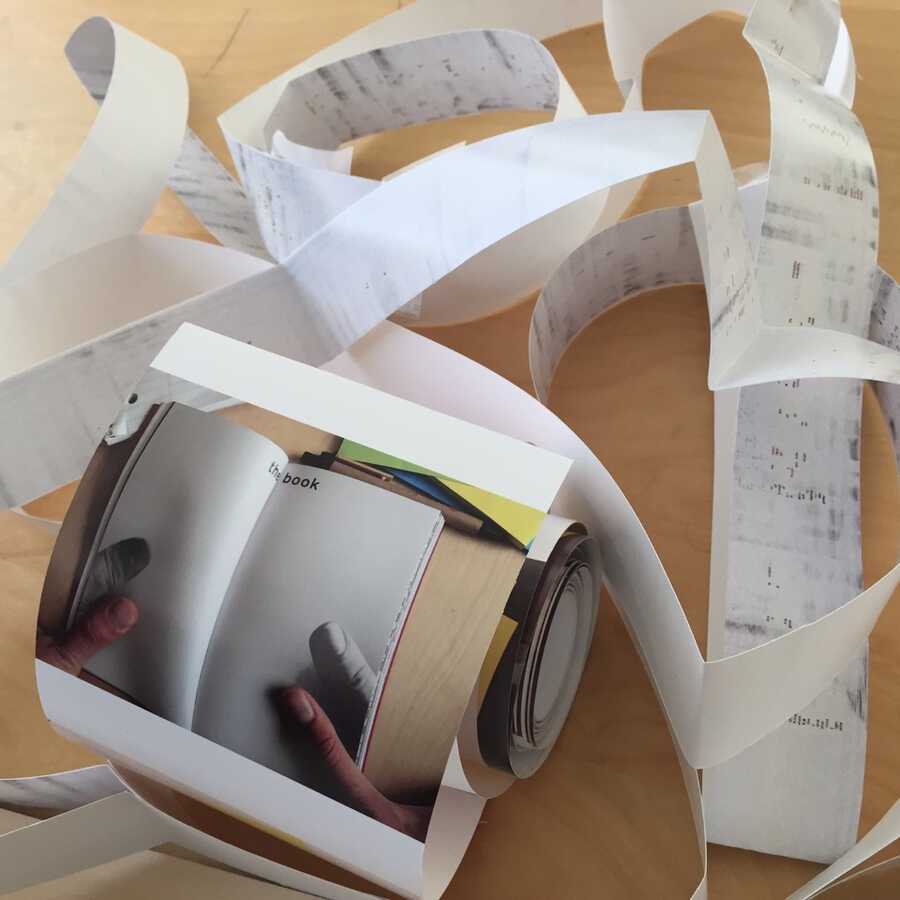

I had the feeling that our presentation went neither well, nor poorly, but that it passed almost completely unnoticed, since it didn’t occur on the elevated demo screen. Dalida wasn’t fully aware of the strictly-enfoced three-minute demo time limit, and presented the codec in a warm expanse of temporal possibility. We raised a few eyebrows when Matthew unfolded the “audio book,” which we had folded in the silences and which therefore was an entirely impractical open-once artifact, and which, as expected, exploded all over the room. Here, behind Matthew and Dany, Codex attendees in the blast radius examine the enigmatic lattices:

We rolled up the book2codex and grabbed the receipt of the conversation to a back room for “intimate” study by anyone who wished a closer look.

I think I only heard one piece of feedback: one designer asked if we were going to throw away the codex, because he thought it was “cute” and he would gladly take it home if that would save it from the scrapyard. We politely declined his offer.

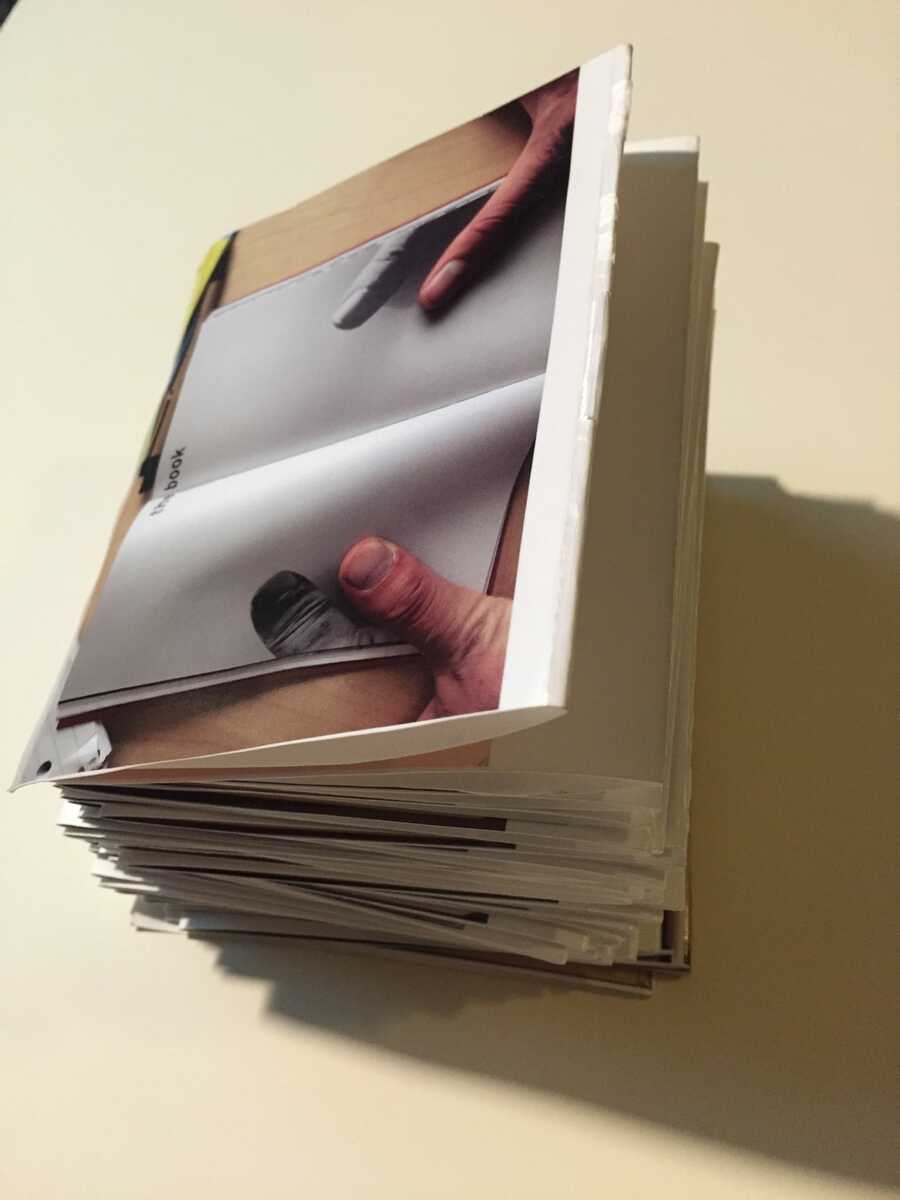

A few days later, I met with Dany to finish cutting out the spare codices we had batched out (to waste less paper). Ever the resourceful engineer, Dany invented a new method and apparatus for the expedient trimming of excessively long codices (15sec, 1.5mb). We evenly folded the remaining codices—Dany’s more even than mine—and I took a few pictures.

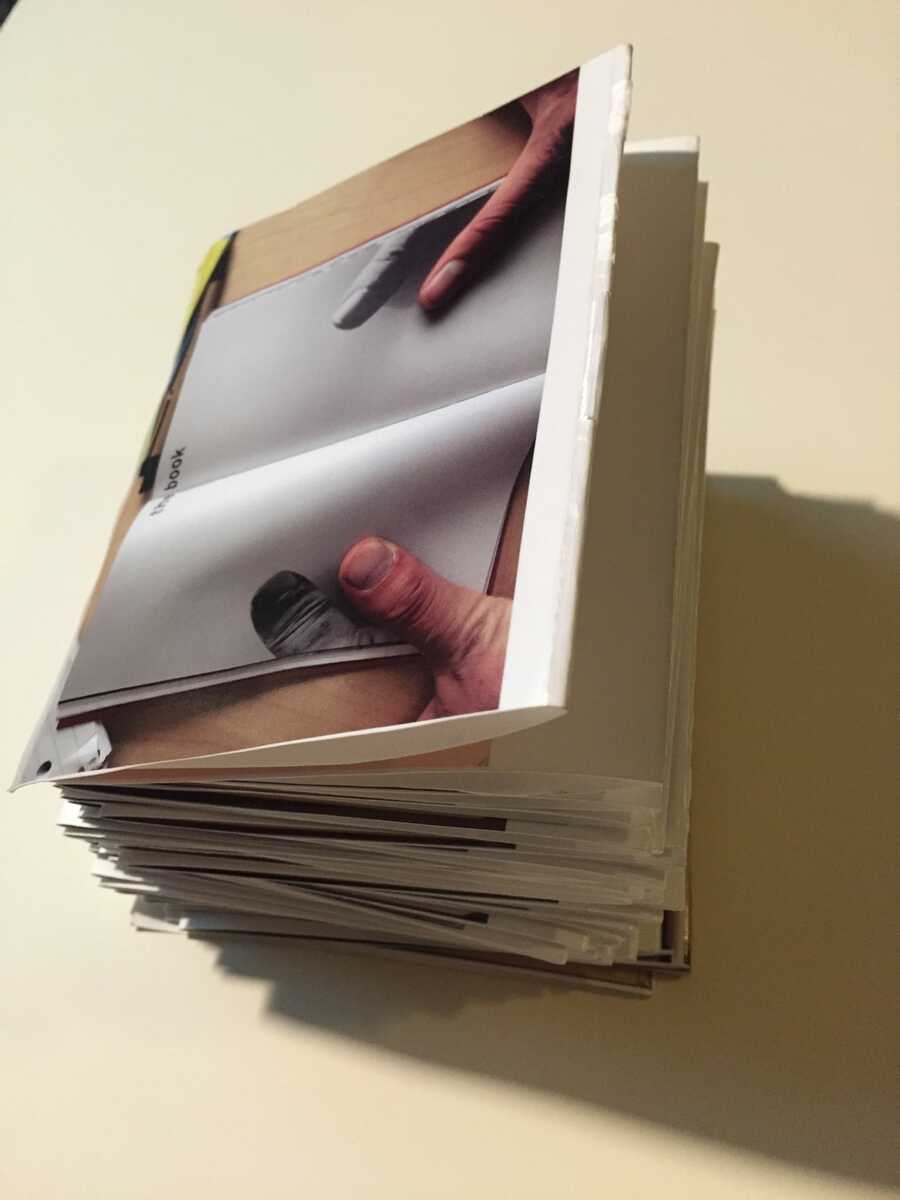

Well-folded, the spectral-lattice book turned into a wieldy, compact volume:

The now-accordion-folded book codex took on a sympathetic clumsiness:

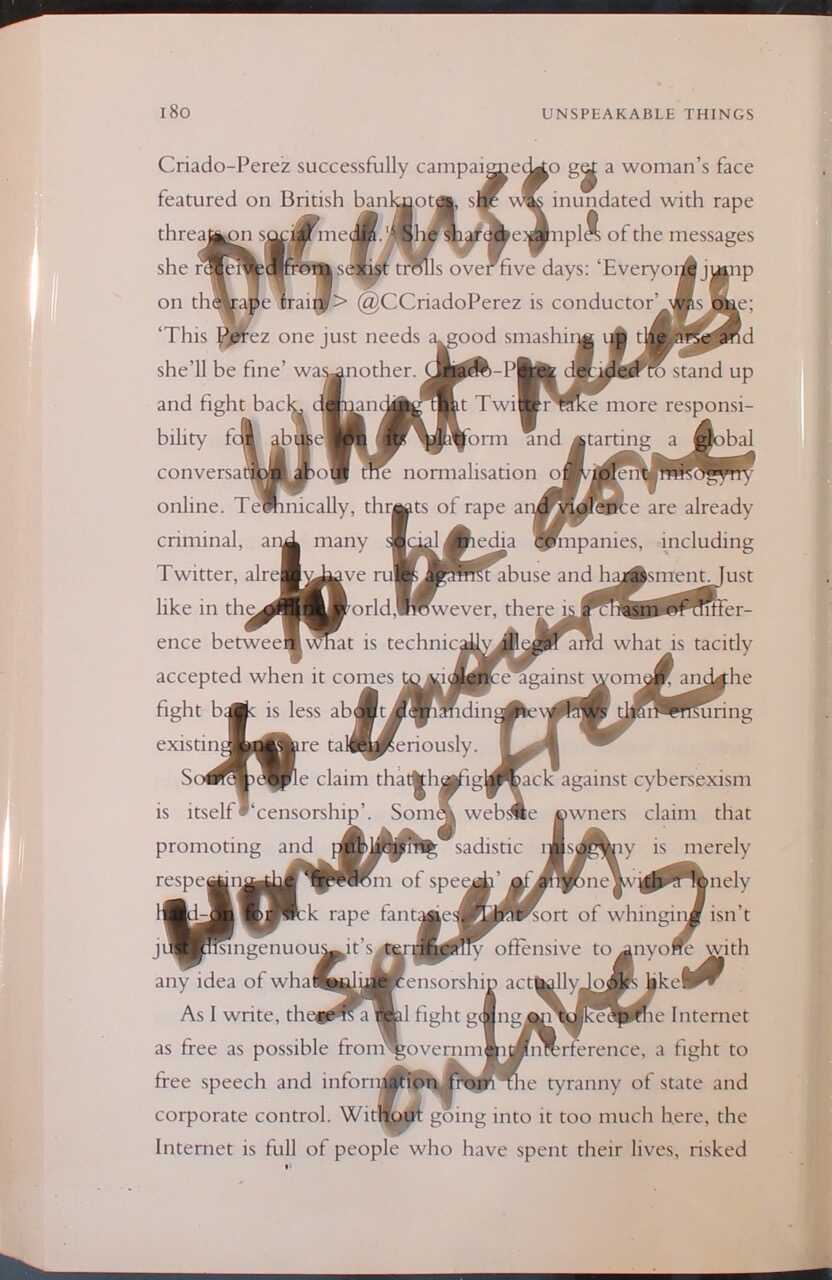

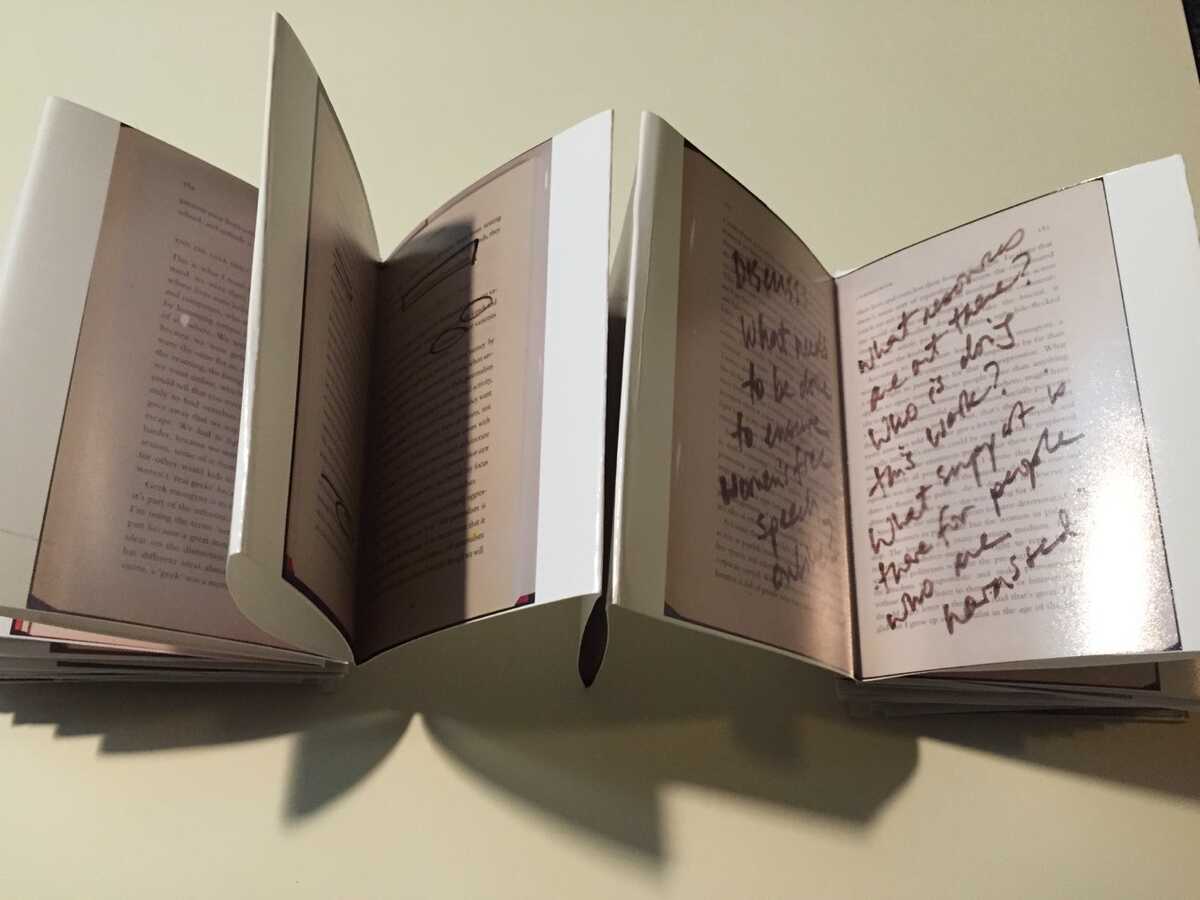

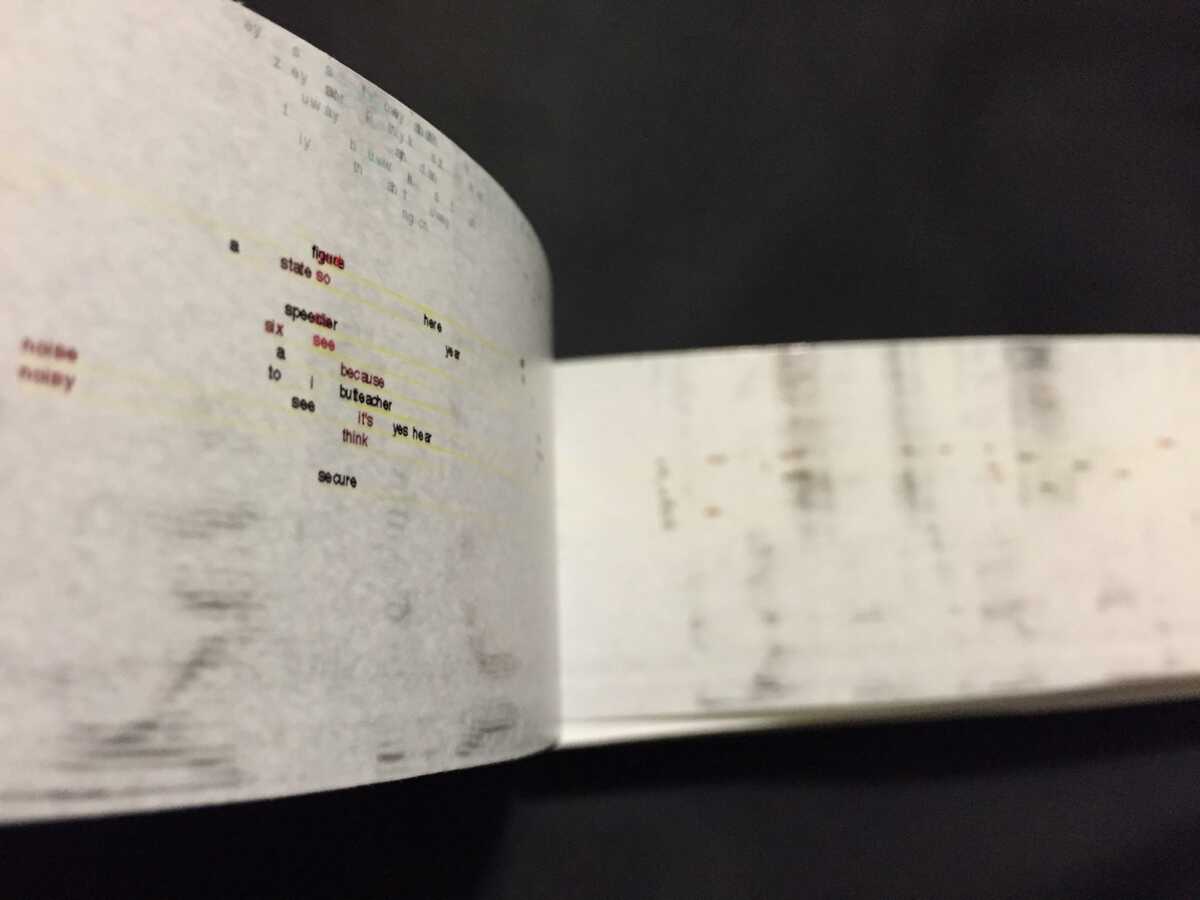

The text and annotations were very much legible:

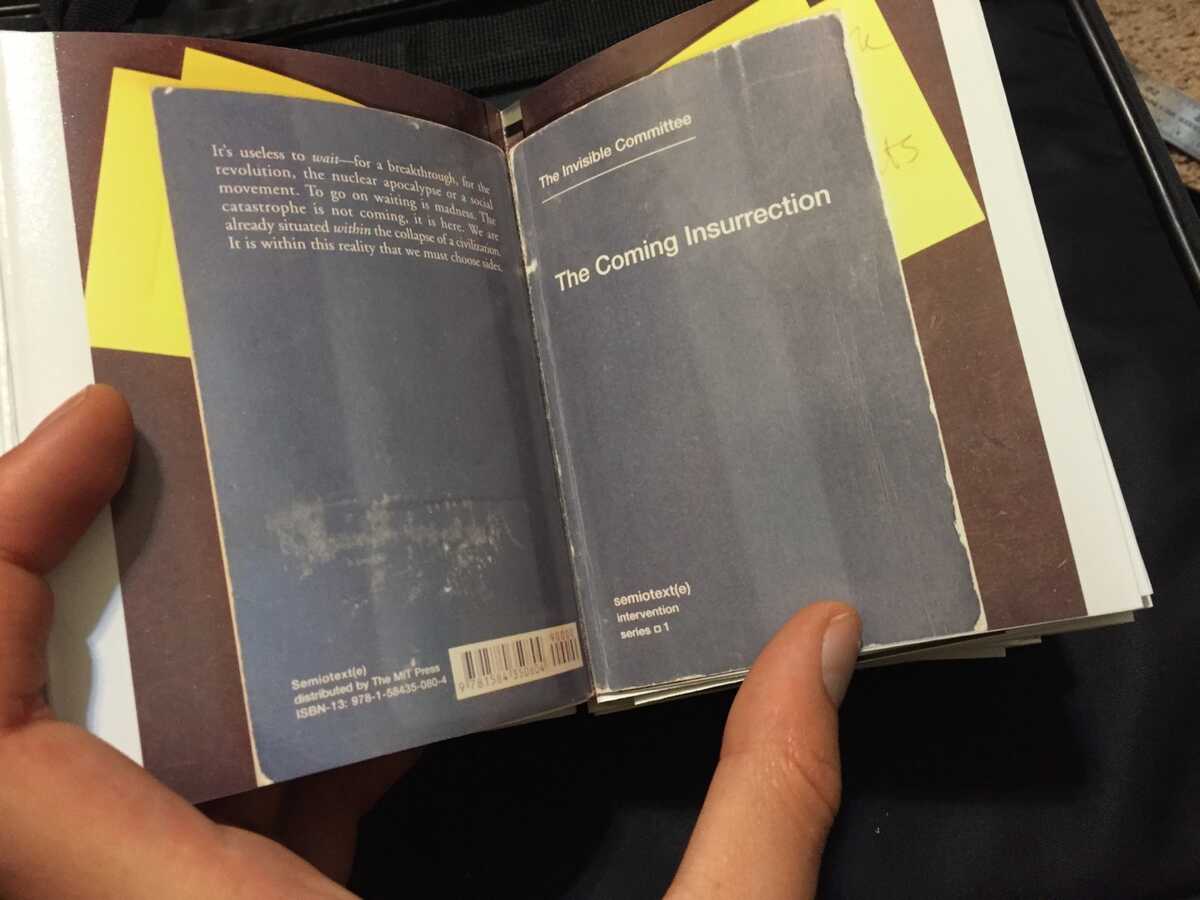

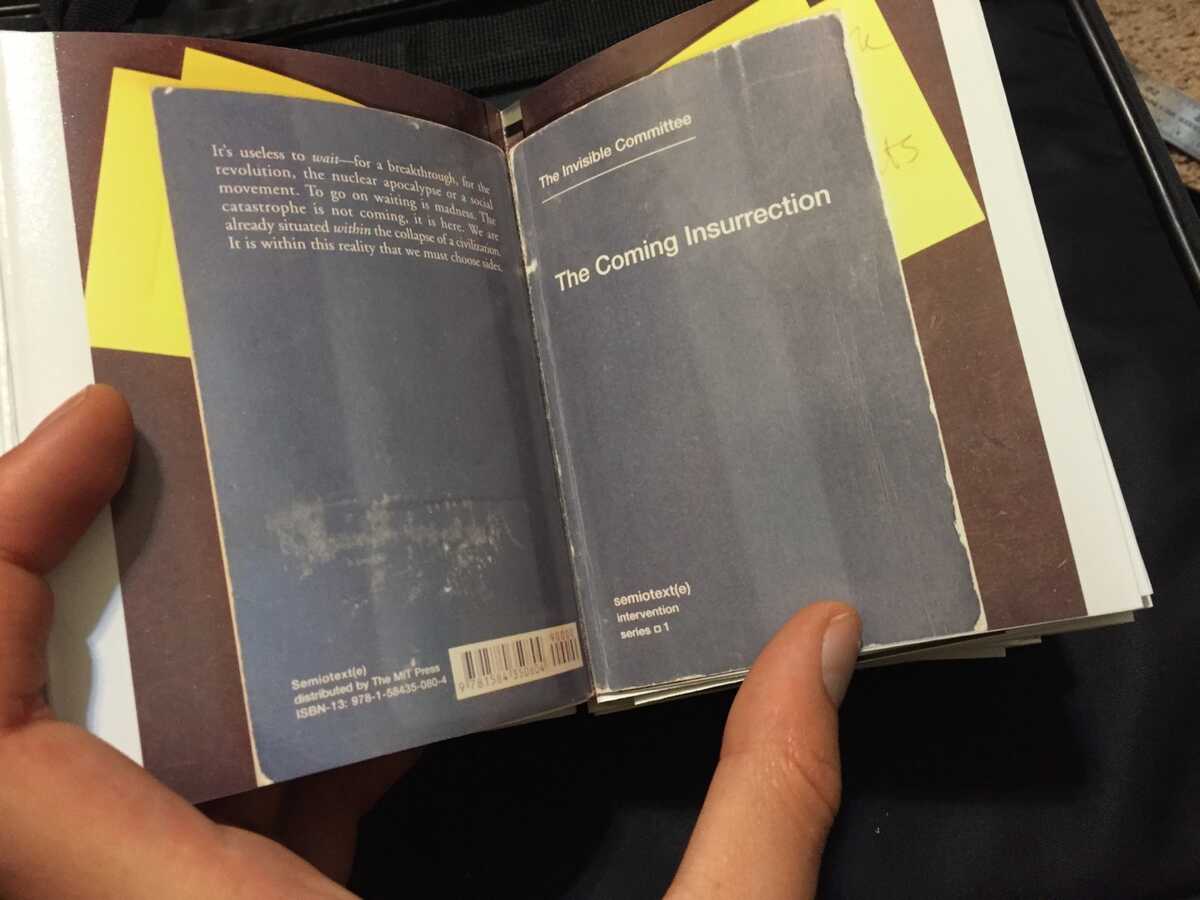

One very funny effect was opening up to the inverted cover of a book we scanned:

… or the laptop, which showed the book scanning interface in-process:

Without binding, unconventional topologies are possible:

…to the extreme:

I love the idea that reading books should produce a new book, and hope to explore that idea further with different modes of interaction and augmentation. The codex is interesting as a form between the scroll and bound volume. With the accordion folding, it can disguise as a book, intimately containing its content, but it can also spring out into a social object—off the screen, beyond the bedroom.

- -

I found the weekend spiritually exhausting, and wouldn’t have managed to persist at Codex without Dalida’s unflappable positive attitude and curiosity. For more reflections, see her blog post.

Your correspondent,

R.M.O.